Sustainability dimensions in goods movement

Sustainability dimensions in goods movement

The section “Sustainability dimensions in goods

movement” provides you with an overview of the three pillars of sustainability

– society, environment and economy – and its importance for goods movement.

4. Economic dimension

On the following page the economic dimension of sustainability will be explained to you. After showing you different providers of transport and logistics services, the transaction cost theory and the resource dependence theory will be explained.

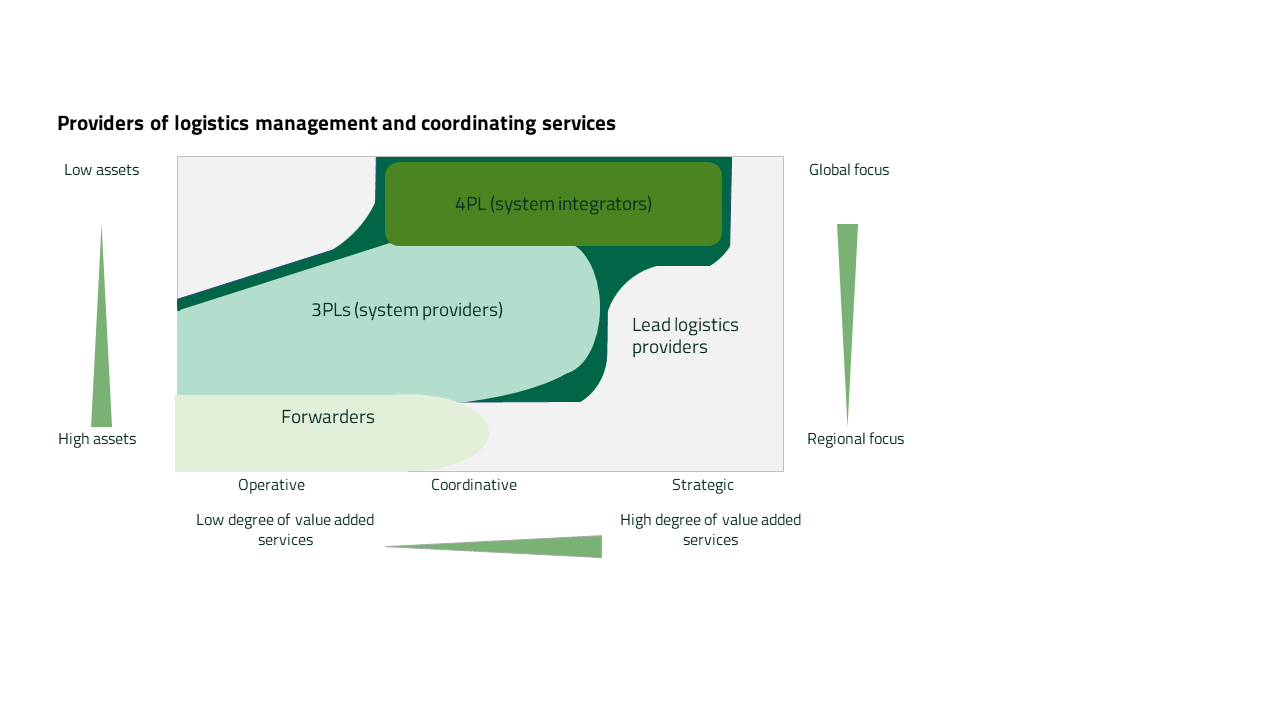

Types of logistics service providers

Logistics service providers are companies that provide logistics services for shippers, whereby the scope of the services provided differs. The following figure “Providers of logistics management and coordinating services” shows the differences between forwarder (2PL), third-party logistics provider (3PL), fourth-party logistics provider (4PL) and lead logistics provider (LLP). The 3PL are system providers, while the 4PL are system integrators. The actors differ in terms of their focus (global or regional), their amount of assets (low or high) and their coordinative (operative (low degree of value-added services) or strategic (high degree of value-added services)). While forwarders have high assets, a regional focus and a low degree of value-added services, the 4PL have low assets, a global focus and a high degree of value-added services.

A Forwarder (2PL) coordinates physical services of transport operators and other core logistics in integrated service package.

A Third-party logistics provider (3PL) operates large logistics networks by combining own and third-party logistics services and combines single services into customer-specific contract logistics service packages. Examples are door-to-door Supply Chains (SCs), complex storage tasks and value-added services as well as third-party Supply Chain Management (SCM)

A Fourth-party logistics provider (4PL) combines logistics services of 2PLs and 3PLs and provides related IT services. He acts on the logistics market without own physical assets.

A Lead logistics provider (LLP) integrates 3PL and 4PL services into LLP services and achieves additional added value by realizing process harmonization and providing a Supply Chain spanning IT-platform. Examples are the coordination of LSPs and suppliers in supply networks, merge-in-transit services, increased consolidation effects in awarding transport volumes to logistics providers, transparency and event-based disruption management.

The "physical" transport and logistics services can be provided by different actors, for example by:

- Container shipping lines

- Seaport terminal operators

- Inland transport operators (road, rail, barge)

- Inland terminal operators

Close and Long-Term Shipper-Logistics Service Provider Relationships

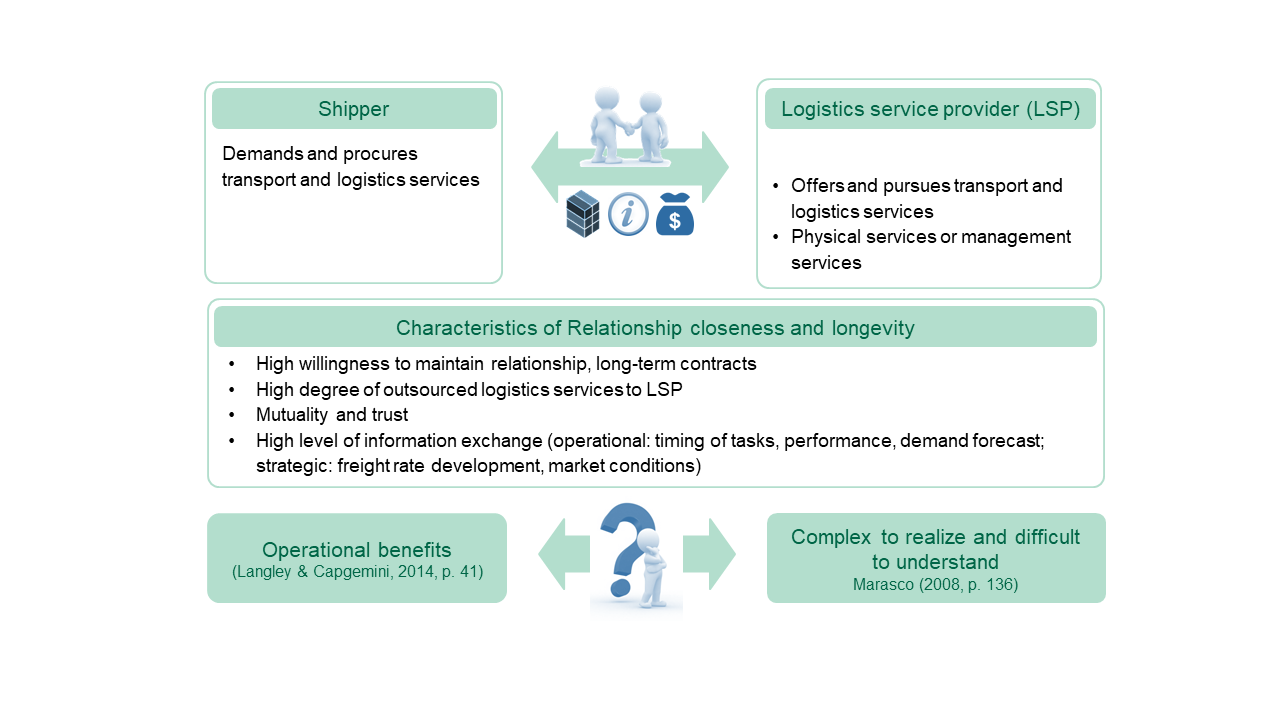

The LSPs described above offer their services to shippers. “Shippers are business firms […] that utilize carriers for the transportation of goods from origin to destination locations.” Examples for shippers are e.g. cargo owners, firms who initiate the transport or to whom delivery is to be made and a shippers’ association. The contractual relationships between shippers and LSP vary and both short-term and long-term contracts are used. The following figure “Close and Long-Term Shipper-LSP Relationships” shows, what a long-term relationship means for the shipper and the LSP. It shows the responsibilities of the shipper (demands and procures transport and logistics services) and the LSP (offers and pursued transport and logistics services (physical or management)) and highlights, that this relationship is characterised by long-term contracts, a high degree of outsourced logistics services to LSP, mutuality and trust such as a high level of information exchange. While this agreement can lead to operational benefits, it is complex to realize and difficult to understand those kind of relationships.

The shipper and LSP have a commercial/contractual relationship and exchange information, cargo and/or financial flows. During the high level of information exchange both operational and strategic data are exchanged. At the operational level, data on the timing of tasks, performance and demand forecast is shared, at the strategic level, data on the freight rate development and market conditions is shared.

The "strong, lengthy and partner-focused relationships with their 3PLs and 4PLs" are needed by shippers "to attain more highly functioning and cost-effective supply chains" (Langley & Capgemini, 2014, p.41) but getting there might be difficult. “The path to achieving these results is not without its difficulties” and [i]mpediments are likely to be encountered in all the different phases of relationship development […].” (Marasco, 2008, p. 136)

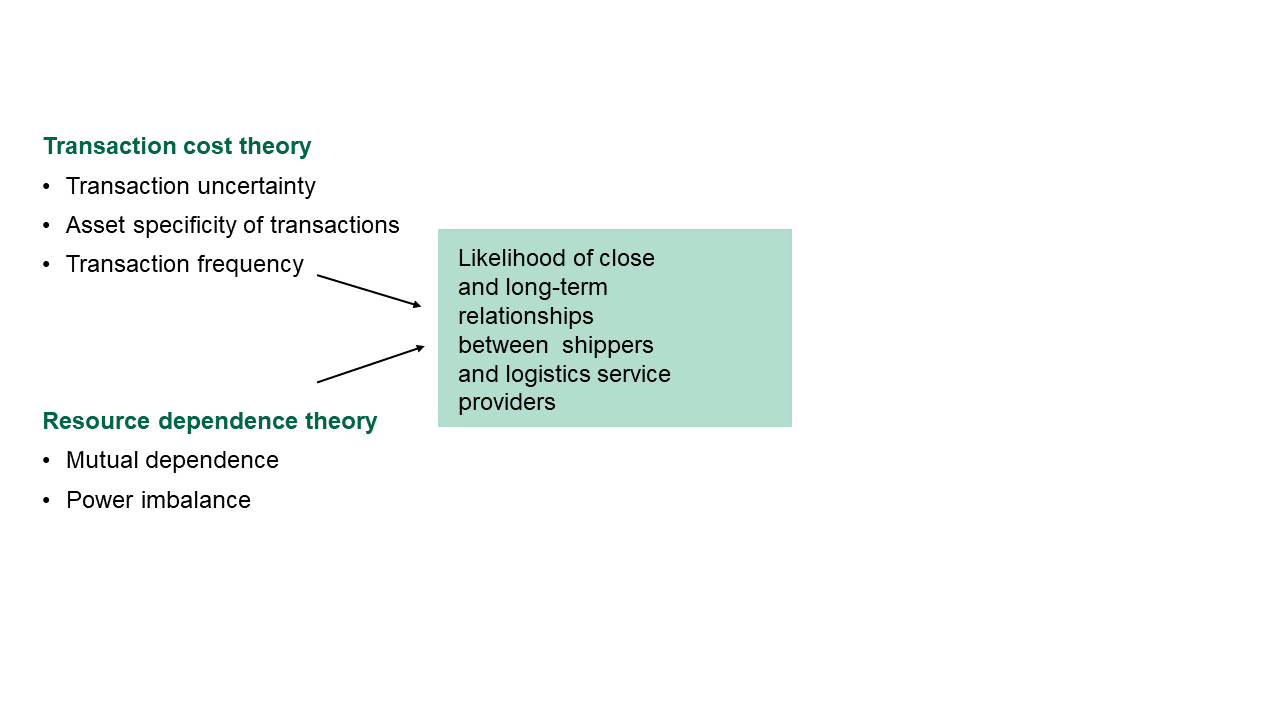

Causal model to explore shipper-LSP relationships

To understand the relationship between shippers and LSPs, a theoretical framework based on organisational theories can be used. This framework utilises transaction cost economics (TCE) and resource dependency theory (RDT). The following figure, "Causal model for analysing shipper-LSP relationships", shows how the two approaches can help determine the likelihood of close and long-term relationships between shippers and LSPs. Information on transaction uncertainty, asset specificity of transactions and transaction frequency is required from transaction cost theory, while results on interdependence and power imbalance are used from resource dependence theory.

The information on the six aspects is explained in detail in the following figure “Attributes of transaction cost economics and resource dependence theory”. While the TCE has an exchange perspective and all three constructs are having a positive influence on the likelihood of close and long-term relationship between shipper and LSP, the RDT has a resource perspective, where the resource and mutual dependence are having a positive association to the likelihood, while the power imbalance has a negative one.

Attributes of transaction cost economics and resource dependence theory, Source: Own figure (CC-BY-SA)

Transaction Cost Economics (TCE)

The TCE determines the most economical type of exchange relationship for each type of inter-firm exchange. The transaction cost theory by Williamson is defined as follows:

- “A transaction occurs when a good or service is transferred across a technologically separable interface” (Williamson, 1981, p. 552)

- TCE is widely used to determine ideal governance structures, that is, “the institutional framework in which the integrity of a transaction is […] decided” (Williamson, 1996, p. 11)

- “The overall object of the exercise essentially comes down to this: for each abstract description of a transaction, identify the most economical governance structure.” (Williamson, 1979, pp. 234-245)

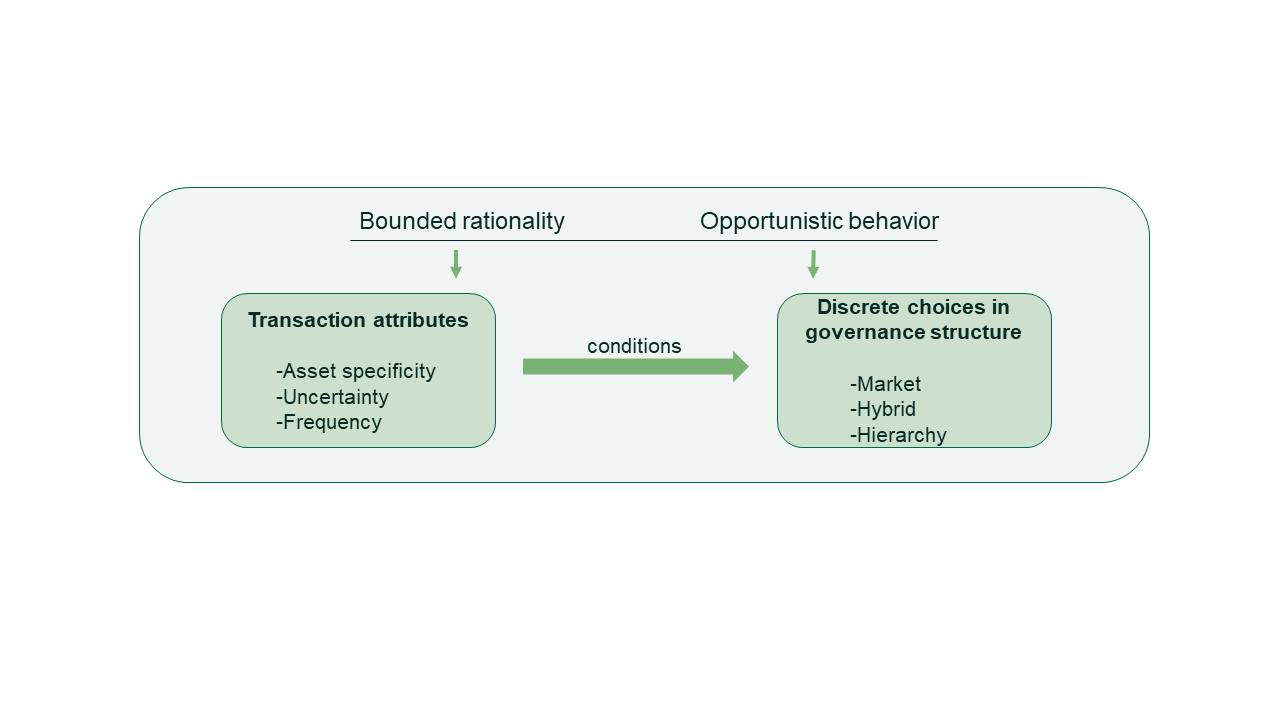

The following figure „Components of transaction cost theory” shows the different transaction attributes (asset specificity, uncertainty and frequency) that are determining the discrete choices in governance structures between hierarchies, hybrid forms and markets. The key behavioral assumptions of the TCE are the bounded rationality and opportunistic behaviour. Because of the bounded rationality, actions might not be rational because of the limited capabilities to process and communicate information by the decision makers. The opportunistic behaviour assumes that "economic actors in contractual relations may take opportunities to dishonestly seek self-interest". This causes a behavioral uncertainty, as the economic actors can "not know, whether contracting parties behave opportunistically" (Herz 2015). The opportunism is more problematic, when the degree of asset specificity (degree to which an asset has a higher value to a specific relationship than outside the relational framework) is high, as the value of those assets is low outside of the relationship. A high asset specificity leads to high incentives to solve problems instead of ending the relationship. There are six types of asset specificity: equipment, site, human assets, facilities, timing of tasks and brand name.

TCE governance modes

There are three TCE governance modes (market, hybrid and hierarchy), that differ in terms of their degree of relationship intensity. While the market governance mode has the lowest relationship intensity, the hierarchy governance mode has the highest. The three governance modes have the following specifications:Market governance

- Recurrent transactions via the market, identity of exchange partners is not important.

- Buyers and suppliers respond to price changes. They decide autonomously to either switch (for little costs) or maintain exchange.

Hybrid governance

- The Identity becomes important. The value of specific assets is closely connected to transaction partner

- Mutual consent needed to react to disturbances (cooperation)

- Legal autonomy of partners is maintained

Hierarchy

- Vertical integration: adaptation by goodwill without interference of other parties

Resource Dependence Theory (RDT)

The RDT is used to build close relationships with exchange partners that allow you to minimize resource dependence. It explores how dependence on external resources affects the distribution of power between actors and ultimately influences its relationship. It also includes the role of environmental contingencies in inter-organisational relationships.

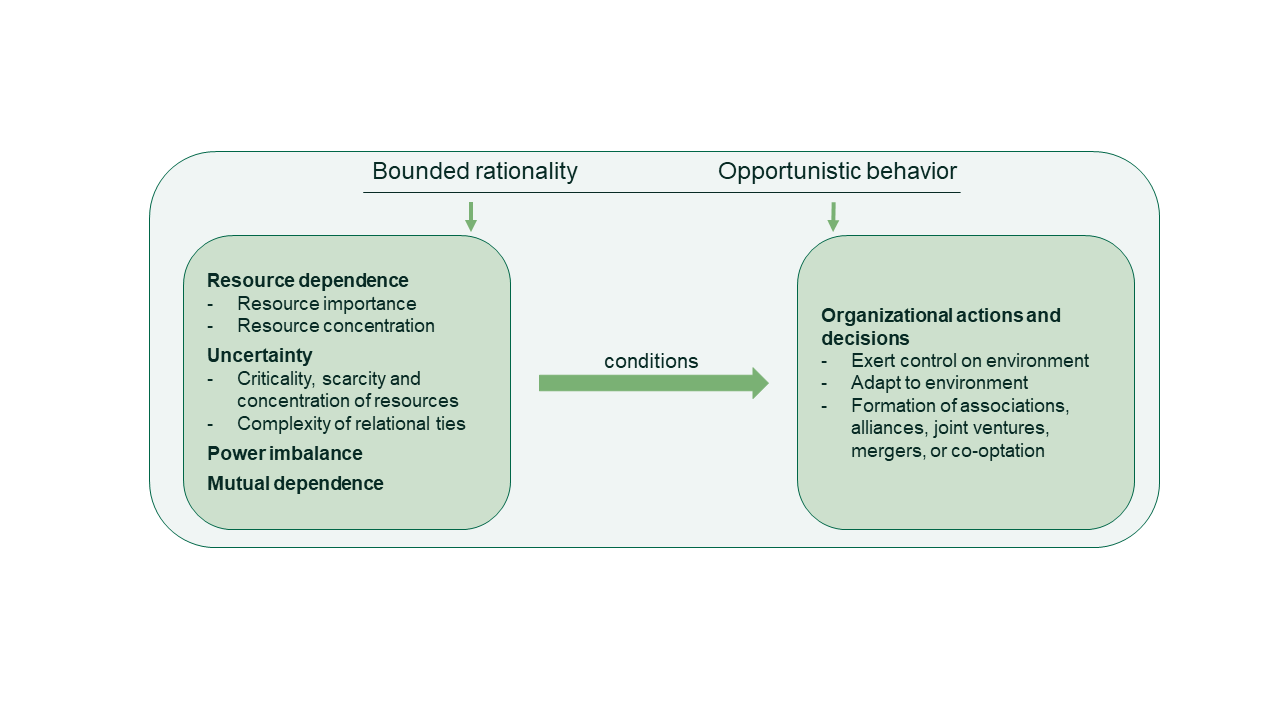

The following figure “Components of resource dependence theory” shows the behavioral assumptions, components (resource dependence (resource importance, resource concentration), uncertainty (criticality, scarcity and concentration of resources, complexity of relational ties), power imbalance and mutual dependence) and the proposed relations of the RDT. The four components are determining the organisational actions and decisions like exert control on environment, adapt to environment and the formation of associations, alliances, joint ventures, mergers or co-optation. Like the TCE, the key behavioral assumptions of the RDT are the bounded rationality and opportunistic behaviour.

RDT Governance modes

There are different strategies to regulate relations with your partners. You should “Choose the least-constraining device to govern relations with your exchange partners that will allow you to minimize uncertainty and dependence and maximize your autonomy” (Davis & Cobb 2006, p. 24). Some tactics forego direct involvement of those who exert dependence, so that organizations adapt to their environment (sourcing diversification, increase firm size). Other strategies directly target the nature of the inter-organizational relationship between dependent parties in order to manage interdependencies and reduce power imbalances and to improve control over strategic resources (alliances, joint ventures, mergers).

Location and Accessibility Matter – Spatial Concentration of Services Creates Lock-In for Shippers

Not only are the LSPs dependent on the shippers, but the shippers can also be dependent on the LSPs. The following figure “Spatial Concentration of Services Creates Lock-In for Shippers” shows a centralisation of a supply network in 2002, which led to a spatial consolidation of goods flows. In this example, the LSP operates the central warehouse and the port on-carriage. This leads to operational advantages for goods inflow (economies of scale, sustainability targets) and goods outflow (increased flexibility through consolidated flows) but creates a high level of dependency for the shipper that is difficult to reverse. The spatial concentration of supply network, location and accessibility of LSP facilities strongly influences shippers’ decisions to engage with and maintain relationships with LSPs.

There exists a close proximity between the trimodal accessible LSP’s facilities and seaports further logistics sites that enables shippers:

- to use mass compatible modes of transport,

- to realize economies of scale in transportation and goods handling,

- to increase operational flexibility by keeping flows consolidated as long as possible.

The shipper-LSP exchange is influenced by the site specific nature of the logistics services pursued and hence depended on the spatial organization of the supply network as a whole. So, in all cases shippers improved SC efficiency and flexibility by keeping flows consolidated as long as possible and by utilizing the close proximity between LSP-operated logistics facilities, seaports and additional logistics sites.

Summary

- Stable and predictable earnings

- Learning effects and know-how development from long-term contract logistics deals to strategically grow in certain logistics fields → reduce cyclicality of business

- Cross-fertilization of other business segments such as port logistics

- Safeguards to reduce own investments in facilities and equipment

- Improved ability to outsource ever larger, more complex and sophisticated logistics tasks

- Realize economies of scale

- Access to LSP’s innovative capacity or to relationship-specific knowledge

- Avoidance of own investment in physical assets

- Secure access to certain valuable resources in the long run that brings certain operational benefits like:

- Logistics services that meet certain quality criteria (e.g. reliability, responsiveness, asset utilization)

- Services provided at concrete locations or guarantee access to certain facilities

- Services that allow to make use of specific transport operators or mass-compatible modes of transport

- Superior information management services

Sources:

Drees & Heugens (2013). Synthesizing and extending resource dependence theory: A meta-analysis. Journal of Management, 39(6), 1666–1698. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206312471391

Herz (2015): Understanding close and long-term relationships between shippers and logistics service providers: A case-based analysis of their determinants and their implications for transaction cost economics and resource dependence theory. Dissertation.

Langley, John, JR.; Capgemini (2014): 2014 Third-party logistics study: The State of Logistics Outsourcing. Results and Findings of the 18th Annual Study. Available online at http://www.capgemini.com/resource-file-access/resource/pdf/3pl_study_report_web_version.pdf (last access 23.12.2014).

Marasco, Alessandra (2008): Third-party logistics: A literature review. In International Journal of Production Economics 113 (1), pp. 127–147.

Talley, W.K. (2009): Port Economics (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203880067

Teece, David J. (1986): Transactions cost economics and the multinational enterprise: An Assessment. In Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 7 (1), pp. 21–45

United States Congress (1984): Shipping Act of 1984 - An Act to improve the international ocean commerce transportation system of the United States. STAT. 67 Public Law 98-237

Williamson, Oliver E. (1979): Transaction-Cost Economics: The Governance of Contractual Relations. In Journal of Law and Economics 22 (2), pp. 233–261.

Williamson, Oliver E. (1981): The Economics of Organization: The Transaction Cost Approach. In American Journal of Sociology 87 (3), pp. 548–577.

Williamson, Oliver E. (1996): The Mechanisms of Governance. 1st ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

Walker & Weber (1984): A Transaction Cost Approach to Make-or-Buy Decisions. Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 29, No. 3. (Sep., 1984), pp. 373-391.