Maritime Transport System

Maritime Transport System

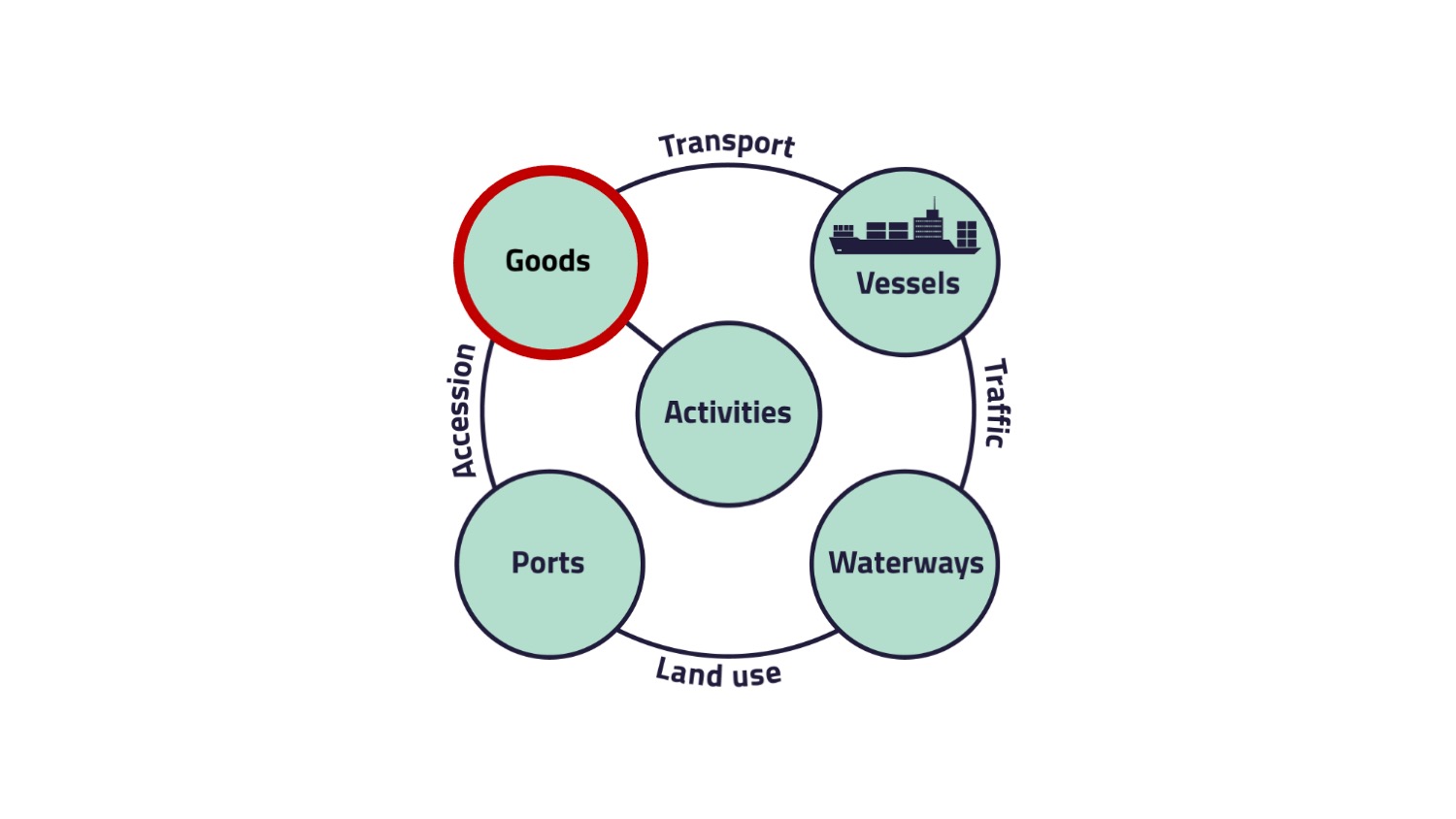

In this section you will learn more about maritime transport and its

elements: activities, goods, vessels, waterways and ports. As in the

last sections, this section follows the structure of the conceptual system model of transport and traffic.

3. Goods

The next element of the conceptual system model deals with the types of goods, being typically transported with the presented mode of transport. We will show you on this page, what types of goods are typically transported by maritime transport.

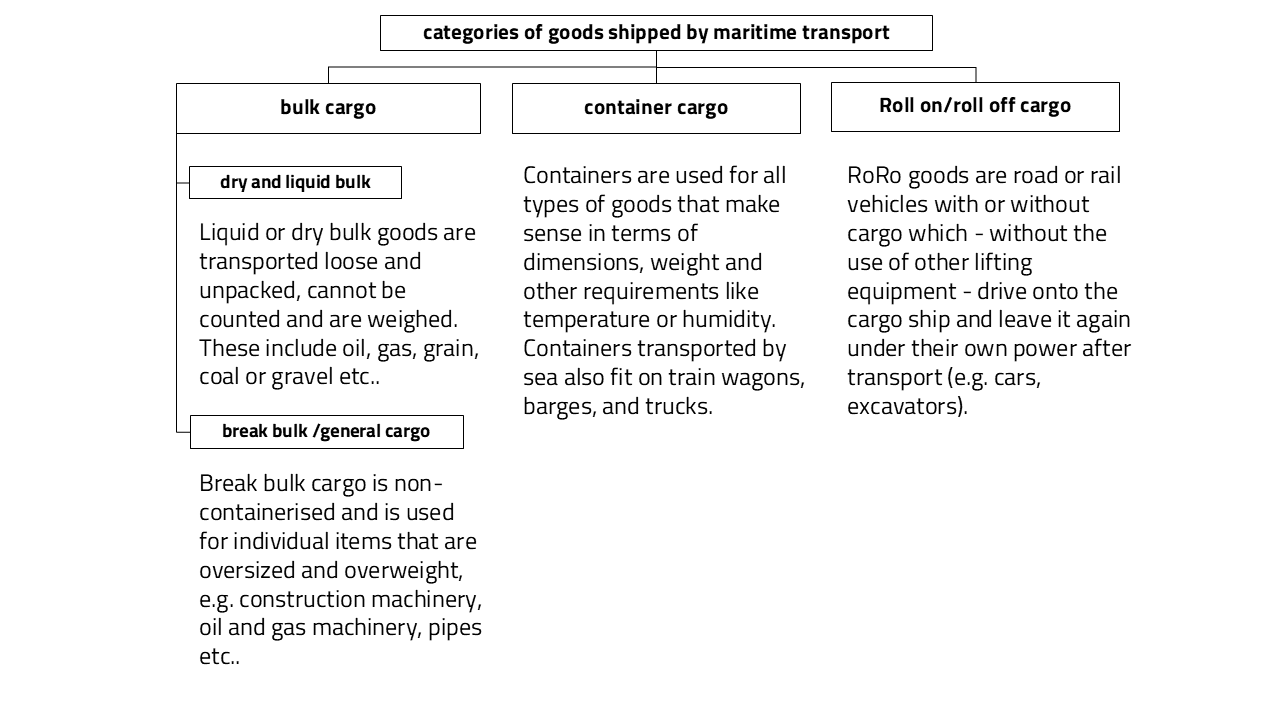

The goods can be divided into three categories:

- bulk cargo,

- container cargo and

- roll on / roll off cargo.

For the transport of goods, the figure "Load carrying devices" shows, what different kinds of loading devices can be used. Those load carrying devices can be differentiated in the categories supporting, enclosing and locking.

For those ground traffic containers, the standard measure is in feet (1 foot = 0,3048 m). An ISO-container is 20 or 40 feet long.

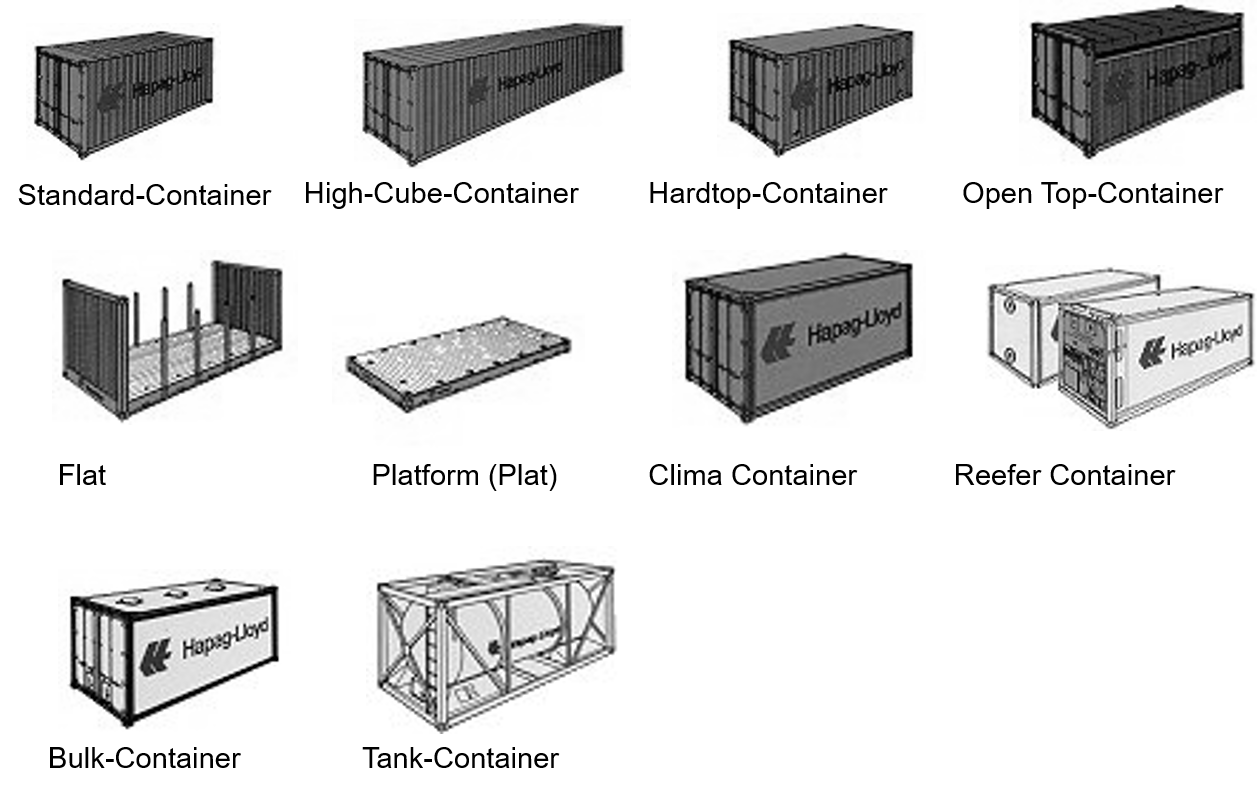

The following figure "Container equipment" shows different kind of ground traffic containers. The kind of goods being transported influences the decision about the container type being used.

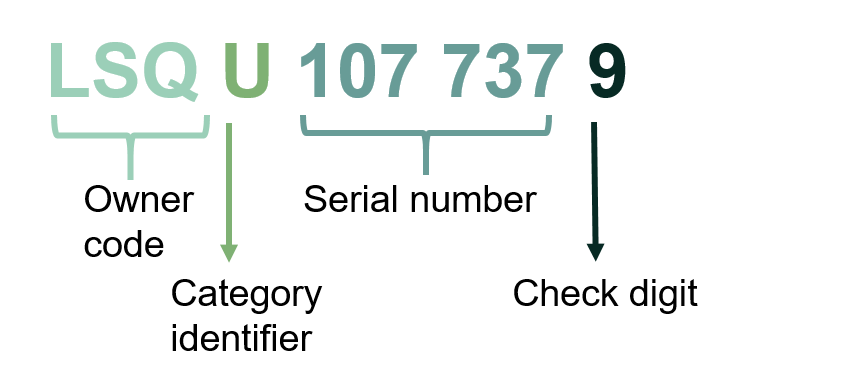

This container number consists of 11 characters.

- The first three letters are showing the owner of the container.

- The fourth letter shows the product category, the U stands for container.

- The first six numbers are the serial number of the container.

- The last number is the check digit.

Containers can be provided by different stakeholders:

- shipping company provides container

- forwarding company provides rented container or

- shippers own container (SOC)

In Maritime Transport, a differentiation is made between Full Container Load (FCL) and Less than Container Load (LCL).

FCL

- volume of freight has sufficient volume for a complete container load

- shipper organizes loading and securing

- containerized transport at least to the port of destination

- volume of freight has insufficient volume for a complete container load

- transport of container part load to Container freight station (CFS)

- consolidation and transport to the port of destination

- LCL service surcharges due to additional handling processes

The ISO-container is a good example for standardization. Advantages of standardization are for example, space utilization, easy handling and safety.

A transport chain with containers has various value-adding roles:

- uniformly unit load (standard size, reusable, stackable)

- high velocity of transhipment process

- internationalization

- reduction of packaging

- suitable for all means of transport

- suitable for inland and overseas transport

If you are interested in the influence of containers on logistics strategies, transport systems and transport chains, feel free to check it here.

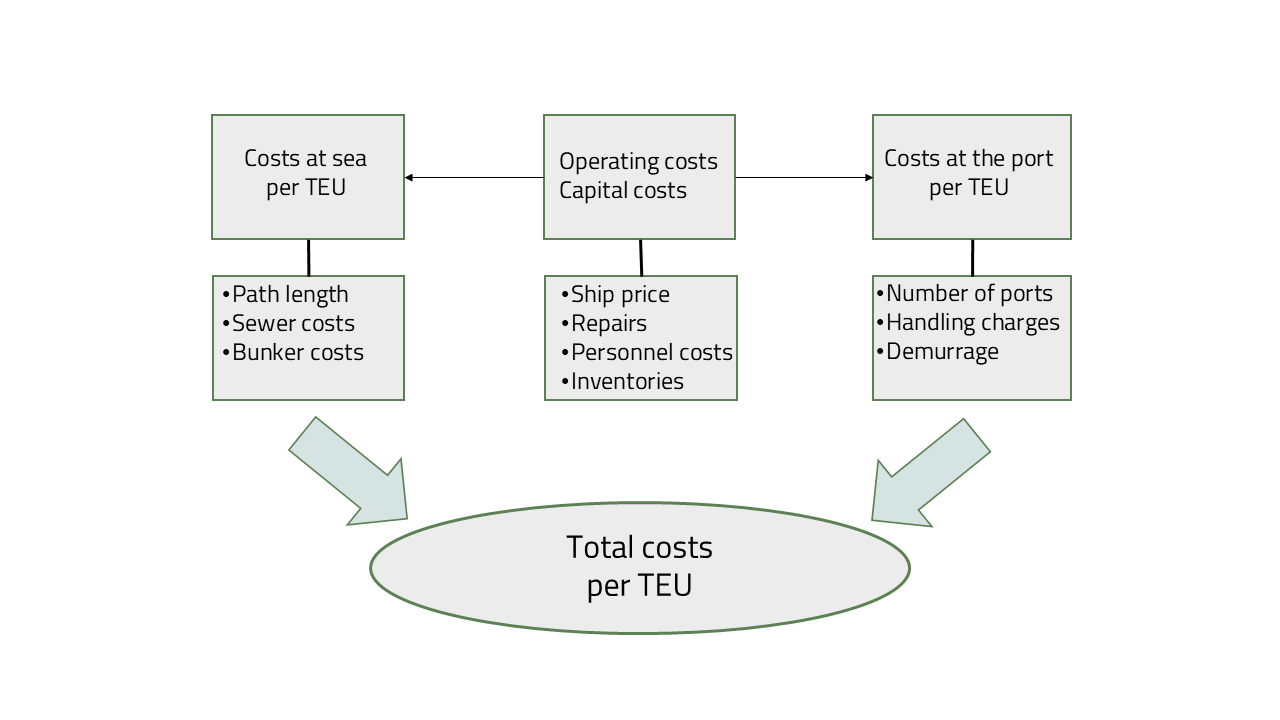

The total costs per TEU are shown in the figure "Total costs per TEU" and are composed of three different elements costs at sea, operating costs and capital costs and costs at the ports.

Transport

Liner service operators

- operational business

- maintenance/survey/storage/supply of vessels

- accounting and market intelligence/viewing

- retail and other business

- Handling of door-to-door transport by carrier on behalf of client.

- Approximately 2/3 of the worldwide transport.

- Independent handling of pre- and subsequent-leg by shipper/recipient or by forwarder on behalf of shipper.

- Normally only pier-to-pier transport.

- The shippers/consignees themselves remain in control and subcontract all involved transport operators. If it's necessary also pier-to-door or door-to-pier transport is possible.

Carrier’s and Merchant’s haulage are shown in the next figure "Carrier's and merchant's haulage".

Door-to-Door Transport (FCL):

Door-to-Pier Transport:

Pier-to-Door Transport:

Pier-to-Pier Transport:

Partners in transportation business

For organizing and operating maritime transport, different stakeholders are necessary.

Some examples for the partners are:

- forwarders

- authorities

- export companies

- import companies

- hauliers

- stevedore companies

- tally

- agents

Biebig, P.; Althof, W.; Wagener, N. (2008): Seeverkehrswirtschaft: De Gruyter Oldenbourg.

Bloech, J. & Ihde, G. (1997): Vahlens großes Logistiklexikon. München: Beck.

Branch, A. (Hg.) (1996): Elements of Shipping. London.

DSV (2023): Break Bulk. URL: https://www.dsv.com/de-de/unsere-loesungen/transportarten/seefracht/breakbulk (last access: 08.05.2023)

Heidenblut V., Hompel M. (2011): Taschenlexikon Logistik

International Forwarding Association (2019): Types of Cargo Shipped by Sea Freight Transport. URL: https://ifa-forwarding.net/blog/sea-freight-in-europe/types-of-cargo-shipped-by-sea-freight-transport/ (last access: 08.05.2023)

ISO (1999): ISO 830:1999-09. Beuth-Verlag, Berlin, 1999.

ISO (2013): DIN EN ISO 6346/A3:2013-03, ISO-Container-Kodierung, Identifizierung und Kennzeichnung. Beuth-Verlag, Berlin, 2013.

Hapag Lloyd (2016): Container Specification. URL: https://www.hapag-lloyd.com/content/dam/website/downloads/press_and_media/publications/15211_Container_Specification_engl_Gesamt_web.pdf (last access: 30.03.2022).

Flämig, H., Sjöstedt, L., Hertel, C. (2002): Multimodal Transport: An Integrated Element for Last-Mile-Solutions? Proceedings, part 1; International Congress on Freight Transport Automation and Multimodality: Organisational and Technological Innovations. Delft, 23 & 24 May 2002. (modification of Sjöstedt 1996)

Grig, R. (2012): Governance-Strukturen in der maritimen Transportkette. Agentenbasierte Modellierung des Akteursverhaltens im Extended Gate. Zugl.: Berlin, Techn. Univ., Diss., 2012. Berlin: Univ.-Verl. der Techn. Univ. Berlin (Schriftenreihe Logistik der Technischen Universität Berlin, 19).

Ihde, G. (2001): Transport, Verkehr, Logistik. Gesamtwirtschaftliche Aspekte und einzelwirtschaftliche Handhabung. 3., völlig überarb. und erw. Aufl. München: Vahlen (Vahlens Handbücher der Wirtschafts- und Sozialwissenschaften).

Jünemann, R. (1989): Materialfluss und Logistik. Systemtechnische Grundlagen mit Praxisbeispielen. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, London, Paris, Tokyo, Hong Kong: Springer (Logistik in Industrie, Handel und Dienstleistungen).

Pawlik, T. (1999): Seeverkehrswirtschaft. Internationale Containerlinienschifffahrt Eine betriebswirtschaftliche Einführung. Wiesbaden: Gabler Verlag (Springer eBook Collection Business and Economics).

Schönknecht, A. (2009): Maritime Containerlogistik. Leistungsvergleich von Containerschiffen in intermodalen Transportketten. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg (VDI-Buch).

Veenstra, A. (2005): Empty container reposition: the port of Rotterdam case. In: Simme Douwe P. Flapper, Jo A.E.E. van Nunen und Luk N. van Wassenhove (Hg.): Managing Closed-Loop Supply Chains. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, S. 65–76.

Voth, M. (Hg.) (2001): Speditionsbetriebslehre. Herne.