Justice⚖

Section outline

-

-

<

Welcome to our episode on Justice. In this episode you will explore fairness and justice in technology design by looking closely at COMPAS - an AI tool designed to predict recidivism, that is, to predict how likely it is that a person who already committed a crime will commit another crime in the future. Using COMPAS, you will learn about the non-neutrality of technology and think about questions like: what data should be included to achieve fair outcomes? Should we use all data or exclude sensitive information to avoid bias?

Welcome to our episode on Justice. In this episode you will explore fairness and justice in technology design by looking closely at COMPAS - an AI tool designed to predict recidivism, that is, to predict how likely it is that a person who already committed a crime will commit another crime in the future. Using COMPAS, you will learn about the non-neutrality of technology and think about questions like: what data should be included to achieve fair outcomes? Should we use all data or exclude sensitive information to avoid bias?

Through the case study on COMPAS, you will explore key concepts associated with justice such as bias, discrimination, and equality, and understand how these principles apply to technology. Finally, you will get to see how philosophical theories of justice can guide us when technical trade-offs are unavoidable. This episode provides a solid foundation for thinking critically about justice and fairness in technology design and practical ways to approach it. -

Let's dive straight into a real-world scenario!

Imagine a courtroom where a judge has to decide whether to release a defendant on bail. The judge considers not only the facts of the case but also a risk score generated by an AI system called COMPAS. This score, produced by analysing various data points, claims to predict the likelihood that a defendant will reoffend if released. The higher the score, the more “risky” the system deems that person to be.

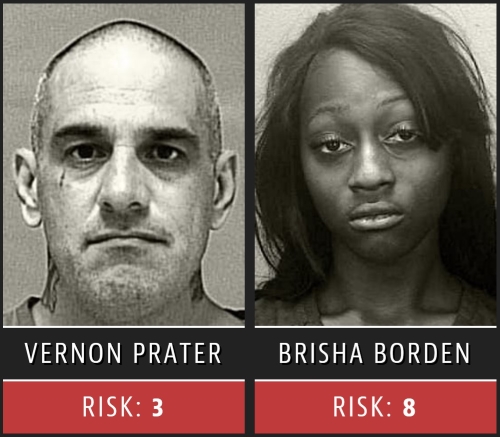

When COMPAS was actually used, it provided risk scores that looked something like this:

Foto credit: https://www.propublica.org/article/machine-bias-risk-assessments-in-criminal-sentencing

This score raised concerns among some, as it assigned a low-risk rating to a white man who turned out to be quite dangerous, while giving a high-risk rating to a woman of colour whose criminal record was far less severe and who did not reoffend. It is, of course, unreasonable to judge an algorithm based on a single instance. Nonetheless, questions emerged: could it harbour bias against individuals of certain ethnic backgrounds or genders?

-

Simply considering that software like COMPAS exists and is in use: Do you think it is a good idea to use it in court?

Please share your thoughts with us below.

-

COMPAS is Real

COMPAS is not a fictional example. It was and is actually in use. ProPublica, a non-profit investigative journalism organisation, published an article about COMPAS in 2016 that went viral and claimed that the algorithm was biased against black people. If you want to learn more about this real-world case and ProPublica's stance, please read their original article, 'Machine Bias'. They also explain their methodology in a separate article that is also worth reading called 'How We Analyzed the COMPAS Recidivism Algorithm'.

Hany Farid discussed the COMPAS case in detail in his TEDx talk. Please go watch it:

External content has been blocked.

You can allow iframes from www.youtube.com to always be displayed immediately. We will store your consent in your browser for this purpose.

The COMPAS case can be seen as a reminder that algorithms, far from being purely objective, can replicate and even magnify human biases. But let's take a step back and break down some of the aspects from the video and our previous claims, starting with the following question: AI systems are basically computer systems working with maths and numbers. So, why aren't they morally neutral anyway?

-

The Non-Neutrality of Technology

Many people assume that technology, especially algorithms, is inherently objective and free from human bias - after all, isn’t it just math?

However, technology is rarely as neutral as it appears.

Every AI system, including COMPAS, reflects a series of human decisions:

- what data to include,

- how to weigh different factors,

- and what outcomes to prioritise

In the case of COMPAS, these decisions have serious consequences, as the algorithm’s risk scores can determine whether someone goes to jail, receives bail, or is released.

Yet the data driving these predictions - such as past arrest records or demographics - often contains existing social biases, which the algorithm can then reproduce or even amplify. This is where ethics by design becomes essential.

Example:

Social media platforms appear to be neutral since they appear to simply provide a way for users to create, share, and react to content. But the algorithms that prioritise and recommend content based on engagement metrics such as clicks, shares and comments are not neutral - they reflect the platform's goal of maximising user attention and advertising revenue. As a result, they often amplify sensational or polarising content because it generates more engagement, even if it spreads misinformation or fuels division.

This demonstrates how technology embeds specific values and agendas, influencing social behaviour and shaping public discourse in ways that are far from neutral.Algorithms won’t automatically be fair or unbiased just because they’re created by computers.

Instead, developers must consciously address and mitigate potential biases during the design process. The stakes are high, and so is the responsibility: in a world where algorithms influence real lives and liberties, we must approach their development with ethics and fairness at the forefront.

Having read that: Let's again look at COMPAS. How does it challenge the belief that technology is neutral? Please share your thoughts below.

-

Now that you know that technology is not neutral, how would you train your software?

The Scope of Training Data

Imagine you’re tasked with designing an AI system like COMPAS, assuming that there is at least the prospect that it could outperform humans on a specific prediction task. But in addition to high performance, you also want the system to be fair, and you’re thinking about the data it will use.

Would you include all data available, including factors like sex and ethnicity (Option A)?

Or would you exclude certain factors to guard against potential bias (Option B)?

Please explore both options.

Option A: Including All Data for Comprehensive Analysis

Option A: Including All Data for Comprehensive AnalysisInformational Maximisation

In this option, you choose to include all available data, including sensitive characteristics like sex and ethnicity. The idea is that by giving the AI system a fuller dataset, it can potentially make more accurate prediction, reduce errors, and, therefore, be fairer overall, as it has access to a complete set of factors that might affect outcomes.We may call this approach informational maximisation.By including a comprehensive range of data, the AI system can “see” a fuller picture, potentially reducing errors and capturing nuances in individual cases. This approach is often supported by an empirical, results-oriented view that prioritises accuracy as a measure of fairness, aiming to minimize mistakes through detailed analysis.

However, informational maximisation also carries the risk of institutionalised discrimination. Including all data may inadvertently embed historical biases in the algorithm, as certain groups may be disproportionately represented in past criminal justice data. As a result, the AI might learn to associate these groups with higher risk, perpetuating systemic biases and reinforcing existing inequalities on an institutional level.

Option B: Excluding Sensitive Data to Avoid DiscriminationInformational Selection

You choose to exclude data on sensitive characteristics such as sex, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status, aiming to prevent discrimination by ensuring the AI is “blind” to these factors. The idea is to eliminate bias by not allowing the algorithm to consider sensitive attributes at all.

We may call this approach "Fairness Through Unawareness" and claim that it could be supported by ideas surrounding liberal neutrality, that is, a system's purported neutrality towards certain aspects of people's personal characteristics or private lives.

This approach emphasises impartiality by suggesting that AI systems should treat individuals equally, regardless of characteristics like race, gender, or socioeconomic status. By excluding sensitive data, the AI avoids directly considering factors that could lead to discrimination. Supporters of this view argue that if the AI does not see protected characteristics, it is less likely to discriminate, aligning with ideals of formal equality where each individual is treated the same.

While this approach of "informational selection" aims to eliminate bias, it does not account for proxy variables. Factors like ZIP codes or income levels can act as proxies for sensitive characteristics, indirectly introducing biases related to race or socioeconomic status. This issue, known as the failure of Fairness Through Unawareness, reveals a limitation in excluding sensitive data. Even without direct references to race or gender, the AI may still develop biased patterns through correlated variables, leading to unfair treatment of certain groups despite the intention to treat everyone equally.

-

-

Selecting the Right Data is Not Enough

As shown with these two approaches of informational maximisation and Fairness Through Unawareness, simply including or excluding certain types of data won’t ensure justice or fairness. We must further investigate fairness metrics to understand how to design systems that genuinely avoid bias.

Before we dive deeper, however, we need to clarify some essential terms.

Understanding these concepts will equip us to evaluate and design AI systems with greater ethical awareness and precision.

BiasBias is a predisposition or inclination - positive or negative - toward a particular group or individual, often shaped by stereotypes rather than actual knowledge or experience. Bias can be implicit (unconscious) or explicit (conscious) and is deeply rooted in human cognition.

In AI, biases in data or design can lead systems to make skewed predictions or recommendations, sometimes without the developers even realising it.DiscriminationDiscrimination refers to actions based on bias, resulting in the unjust or prejudicial treatment of people based on categories such as race, age, or gender.

Discrimination can take many forms, including direct (explicitly unequal treatment), indirect (when policies disproportionately affect certain groups), institutionalised (embedded within systems or policies), structural (rooted in broader social inequalities), and even “affirmative” (intended to correct historical imbalances).JusticeJustice in the context of AI refers to the fair and impartial treatment of all individuals, ensuring that systems do not unduly advantage or disadvantage any group.

It includes notions of fairness, equity, and the safeguarding of individual rights, and challenges AI designers to create systems that uphold these principles.EqualityEquality involves treating all people with the same consideration and opportunity, regardless of their background or characteristics.

In AI, equality means striving for systems that provide consistent and fair outcomes across different demographic groups. -

-

How to ensure Fairness?

In the section on the scope of training data, we explored two attempts to ensure fairness, but saw that this was not enough. Now that we've clarified some important concepts, let's go back to looking for a way to ensure fairness in the development process.

Fairness Metrics

In the COMPAS system, Brisha Borden and Vernon Prater were two individuals who received very different risk scores. Borden, a young woman of African-American descent, was rated high risk, while Prater, a middle-aged white man with a longer criminal record, was rated lower risk. But we can’t really say much on the basis of one prediction. So, how can we actually test for bias in an algorithm?

Let's dive deeper into the tools and concepts we can use to assess whether an AI system, like COMPAS, is actually fair.

These tools are known as fairness metrics, and they help us examine how the algorithm performs across different groups.

Fairness metrics are essential in identifying potential discrimination and helping us understand where an algorithm might be biased. Here are the two most common fairness metrics we use in AI ethics:

The first metric is accuracy, or how often the algorithm makes correct predictions.

For COMPAS, this would mean the percentage of times it correctly predicts whether or not someone will reoffend.

Error Rate Balance is about comparing the types of mistakes the algorithm makes across different groups. Specifically, we look at false positives and false negatives for each group.

False Positive: When COMPAS predicts someone will reoffend, but they don’t.

False Negative: When COMPAS predicts someone won’t reoffend, but they do.This analysis shows that even if the algorithm is very accurate for all groups, it could still make different types of mistakes for different people. For one group, it might mostly label people as high risk when they aren’t dangerous (false positives), while for another, it might label people as low risk when they are dangerous (false negatives).

This difference really matters on a personal level: the effect on someone’s life is very different if they are wrongly released or wrongly kept in detention.

-

Calculating Fairness

Let's look at a dataset from COMPAS to see how discrimination can creep into a technology unnoticed, and to see that discrimination, at least in this case, can be determined mathematically.

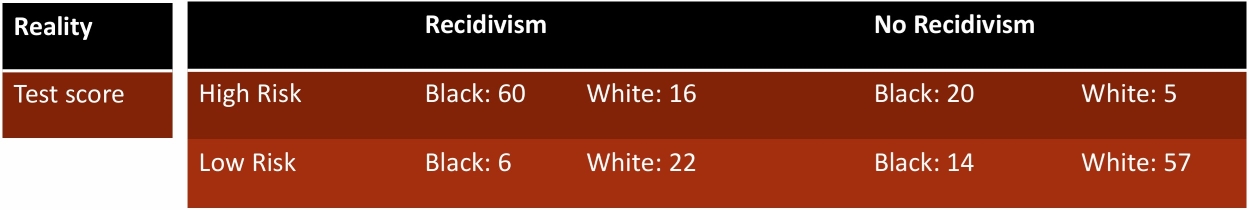

The following table shows in the first line ("reality") whether or not the persons assessed by COMPAS actually recidivised.

The second and third lines ("test core") show the COMPAS scores for blacks and whites (high or low risk of reoffending).

So, let's apply the two metrics: accuracy and error rate balance.

-

Calculating Fairness

1. Accuracy

Let’s begin with accuracy by asking: how often does the algorithm make correct predictions for each group? To measure this, we use conditional probabilities, starting with the positive predictive value (PPV). This refers to the probability that someone actually reoffends (recidivates) given that they have been assigned a high-risk score by the algorithm.

We can also examine this question from the opposite angle, using the negative predictive value (NPV). This measures the probability that someone does not reoffend, given that they have been assigned a low-risk score.

By applying these calculations to the data in the table above, we can determine how well the algorithm performs in these two specific areas. The results give us insight into whether the algorithm is equally accurate for different groups or if there are discrepancies that need to be addressed.

Here are the calculations:

Positive Predictive Value

Black: P (Recidivism | High Risk): 60/(60+20), 0.75

White: P (Recidivism | High Risk): 16/(16+5), 0.76

Negative Predictive Value

Black: P (No Recidivism | Low Risk): 6/(6+14), 0.70

White: P (No Recidivism | Low Risk): 1- (22/(22+57), 0.72

It seems the algorithm performs similarly for both groups, with no clear indication of bias. But is that truly the whole story?

2. Error Rate Balance

Now let’s explore a second important metric: error rate balance. This helps us understand the kinds of mistakes the algorithm makes when it gets things wrong. Are its errors more often false positives (labeling someone as high risk when they are not) or false negatives (labeling someone as low risk when they are actually dangerous)?

To calculate these numbers, we take a slightly different approach to the conditional probabilities we used earlier. Previously, we asked about the probability of recidivism (reoffending) given a high-risk score. Now, we reverse this perspective: we ask about the likelihood of a high-risk score, given that someone actually did reoffend.

Similarly, from the negative perspective, instead of asking about the likelihood of no recidivism based on a low-risk score, we now consider the likelihood of receiving a low-risk score, given that someone did not reoffend.

By looking at these reversed probabilities, we can better understand whether the algorithm treats mistakes equally across groups or if there are imbalances that might reflect underlying biases. When use our data from above, we get the following results:

Positive Error Balance

Black: P (High Risk | Recidivism): 60/(60+6), 0.91

White: P (High Risk | Recidivism): 16/(16+22), 0.42

Negative Error Balance

Black: P (Low Risk | No Recidivism): 14/(20+14), 0.41

White: P (Low Risk | No Recidivism): 57/(57+5), 0.91

Now we can see a significant difference between the groups. For the Black group, the most frequent errors are false positives—being labelled as high risk when they are not. In contrast, for the White group, the most common errors are false negatives—being labelled as low risk when they are actually dangerous.

As we discussed earlier, this difference has a profound impact on individuals. Imagine being detained without justification—falsely labelled as a danger to society. Now compare that to being wrongly released when you actually posed a risk. The consequences, both emotionally and practically, are vastly different depending on which mistake is made.

So, COMPAS had a significant bias in the end: even though the accuracy rate was equal across group, the error rate balance was not.

Unfortunately, we cannot maximise accuracy and equal error rates at the same time:

-

-

What to Do Now?

What can we learn from this? If we want to develop and use technology in areas as sensitive as legal decision-making processes, most people agree that these technologies should be fair. But ensuring fairness is complicated. Selecting the 'right' data is important but can't garantee fairness alone. We have also learned about fairness metrics that mathematically identify potential problem areas.

The question now is how to implement these results in algorithms. -

Impossibility Theorem

It is mathematically impossible for an algorithm to meet all fairness goals at the same time. In the case of COMPAS, this means we cannot achieve both high accuracy for all groups and an equal ratio of false positives (wrongly labelled as high risk) and false negatives (wrongly labelled as low risk) for everyone. We must decide what to prioritise: overall accuracy or fairness in error rates.

This challenge is called the Impossibility Theorem.

It happens because of differences in what are called base rates in the data used to train the algorithm. Base rates show how often something, like reoffending, actually happens in each group. However, these rates aren’t always a reflection of individual behaviour alone—they can be shaped by structural injustices.

For example, if one group has a higher reoffending rate, it may not be because of personal choices alone. It could be linked to systemic issues, like biased policing, unequal economic opportunities, or access to education, which unfairly impact certain communities. Since AI systems rely on historical data, these injustices can end up embedded in the algorithm, making it harder to ensure fairness across groups with different base rates.

As a result, trying to meet one fairness goal (like equal error rates) may come at the cost of another goal (like accuracy), because of these built-in inequalities.

This means that the people who design algorithms face difficult ethical decisions. Under the conditions of our morally imperfect world, they must choose which fairness goals to prioritise, knowing that it is impossible to achieve a perfect balance while the data itself is shaped by wider inequalities in society.

-

What to Prioritise?

What should we do: prioritise accuracy (option A) or error rate balance (option B)? This is a decision that developers face, and thus an important aspect of ethics by design.

Please explore these two options, which show how philosophical theories of justice can help in the decision-making process.

-

-

Final Reflection: Balancing Burdens and Benefits in AI Design

As we conclude this episode on algorithmic discrimination, consider the complex web of values that shape how we develop and deploy AI systems. Technologies like AI hold great promise for improving efficiency, accuracy, and decision-making in fields from criminal justice to healthcare. However, they also carry significant ethical implications, particularly in how they distribute burdens and benefits across different groups in society. When we design algorithms, we confront unavoidable conflicts in values, where maximising one goal, such as accuracy, may mean compromising another, like fairness.

In an ideal world, we would create systems that are perfectly fair, accurate, and respectful of every individual’s dignity. But in reality, ethical design often involves difficult trade-offs. We cannot meet all requirements simultaneously; maximising overall accuracy might lead to imbalances in error rates across demographic groups, while striving for equal error rates might reduce overall accuracy and compromise other societal goals, like safety or resource efficiency. This tension raises fundamental ethical questions:

How should we weigh individual rights and collective benefits in AI design? Should we prioritise aggregate benefits, as a consequentialist might suggest, or should we ensure fairness and equal treatment even if this affects overall efficiency, as a Rawlsian perspective would advocate? Reflect on how these choices impact individuals differently and consider who benefits and who bears the burden of each approach.

What is the ethical responsibility of AI developers in an imperfect world? In cases where achieving absolute fairness or perfect accuracy is impossible, AI developers must navigate a landscape of compromise. How can they ethically justify the choices they make? Should the aim be to minimise harm, maximise benefit, or balance both as equitably as possible? This question invites reflection on the broader societal and moral obligations that come with creating technology.

How might tech developers and the public co-create AI to mitigate risks? Reflect on ways that developers and the public might collaborate to co-create AI tools that are both effective and socially responsible. This could involve public consultations, citizen panels, or pilot testing in affected communities. Consider: How might this collaboration help identify potential biases, clarify ethical trade-offs, and ensure that AI systems are aligned with community values and needs?

As users of AI in today’s world, you have the power to shape the ethical landscape of technology. Be vigilant—ask how these systems are designed, and demand transparency, fairness, and accountability from developers. Your role isn’t passive; by questioning and advocating for ethical AI, you can help ensure that these technologies respect individual rights, address societal needs equitably, and align with shared values. In doing so, you contribute to a future where AI supports a fairer, more responsible world.

-