3.4 Hydrogen Supply Chains

| Website: | Hamburg Open Online University |

| Kurs: | Green Hydrogen |

| Buch: | 3.4 Hydrogen Supply Chains |

| Gedruckt von: | Gast |

| Datum: | Samstag, 14. März 2026, 05:23 |

Beschreibung

After you have learned about the different technologies for storing and transporting hydrogen in the previous two sections, you will learn in this last part of the chapter what future supply chains for green hydrogen could look like. The term hydrogen supply chain describes the entirety of all process steps and the technologies applied between the production of the initial raw materials (e.g. renewable electricity) and the end use of the hydrogen or the derivative.

1. Supply chains

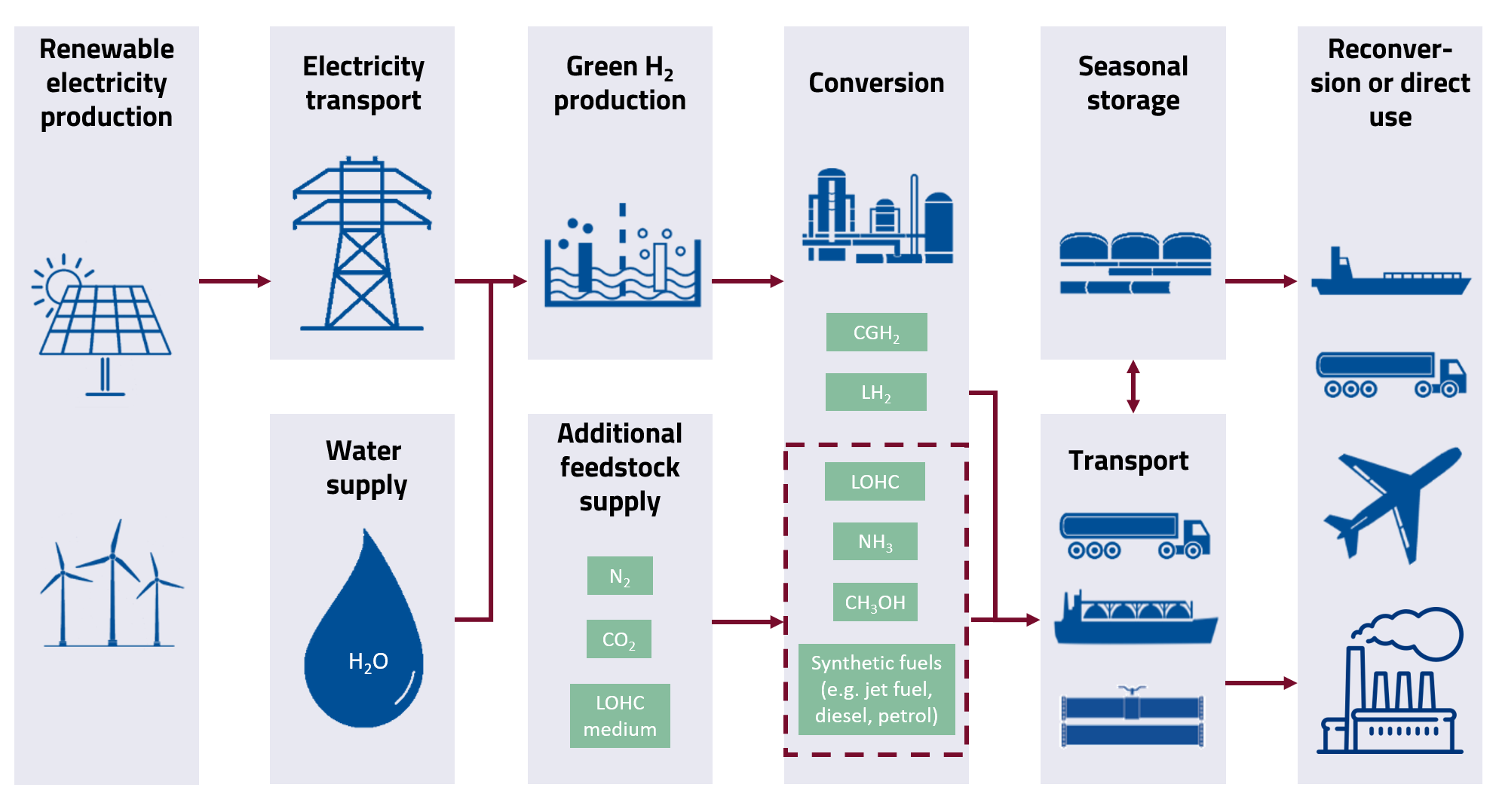

The general components of green hydrogen supply chains are shown in the figure below. The production of hydrogen via electrolysis is the central element of all supply chains. Renewable electricity and treated water are needed for the electrolytic production of green hydrogen. Usually, the hydrogen cannot be consumed directly at the place of its production. Therefore, the next step in the supply chain is conditioning for storage or transport (see 3.2 Hydrogen Storage). The type of this conditioning depends on the form in which the hydrogen is to be transported and stored. If ammonia, methanol or a synthetic fuel is produced, additional feedstock substance (carbon dioxide or nitrogen) is needed in addition to electrical energy and water. If LOHCs are used for the storage and transport of hydrogen, a respective carrier liquid is needed.

To illustrate this, three supply chains for providing different consumers with green hydrogen or its derivatives are presented in the following. Since, as already mentioned, there are currently no supraregional supply chains for green hydrogen, the examples presented here only illustrate possible future scenarios that are realistic from today's perspective.

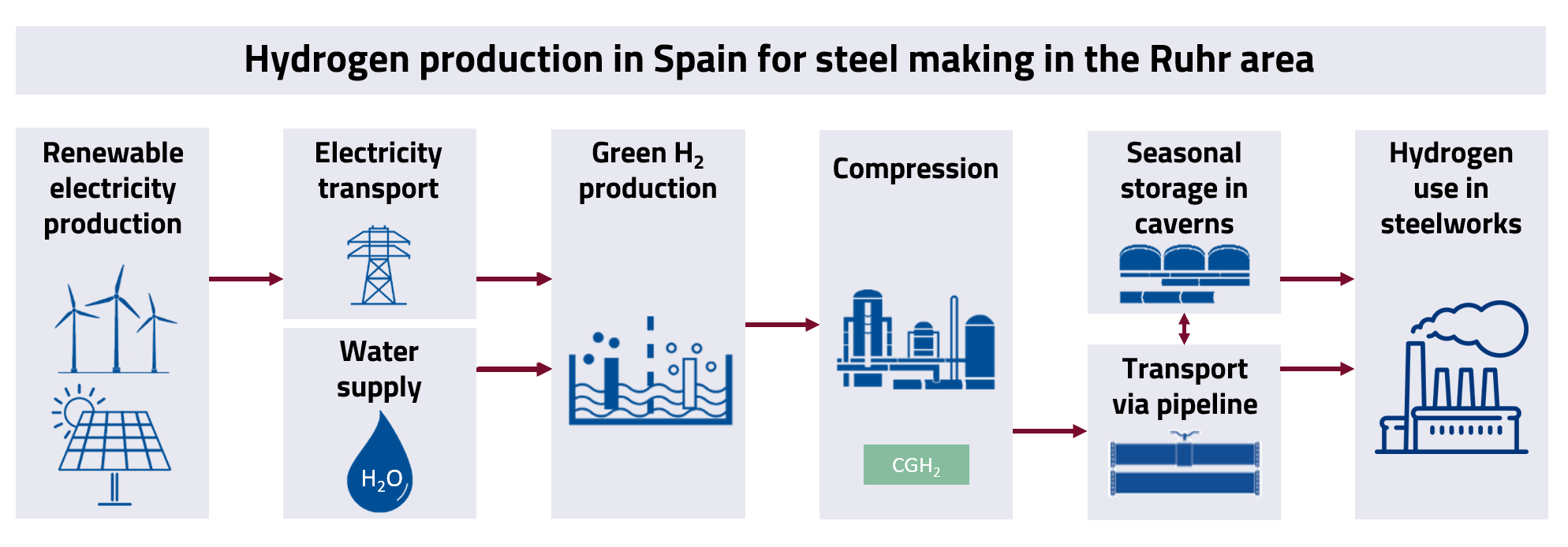

2. Example 1: Storage and transport of compresses hydrogen

As explained in Chapter 3.1, Germany will probably not be able to cover its hydrogen demand completely by itself. Importing by pipeline from sun-rich regions in Southern Europe and North Africa is a possible alternative. In order to make such an import possible, a transnational network of hydrogen pipelines must be established. Numerous operators of natural gas pipelines from various European countries have joined forces for this purpose and want to set up the so-called European Hydrogen Backbone (for further information click here) by 2040, which is to enable the transport of hydrogen from North Africa or Southern Europe via Spain or Italy to Sweden.

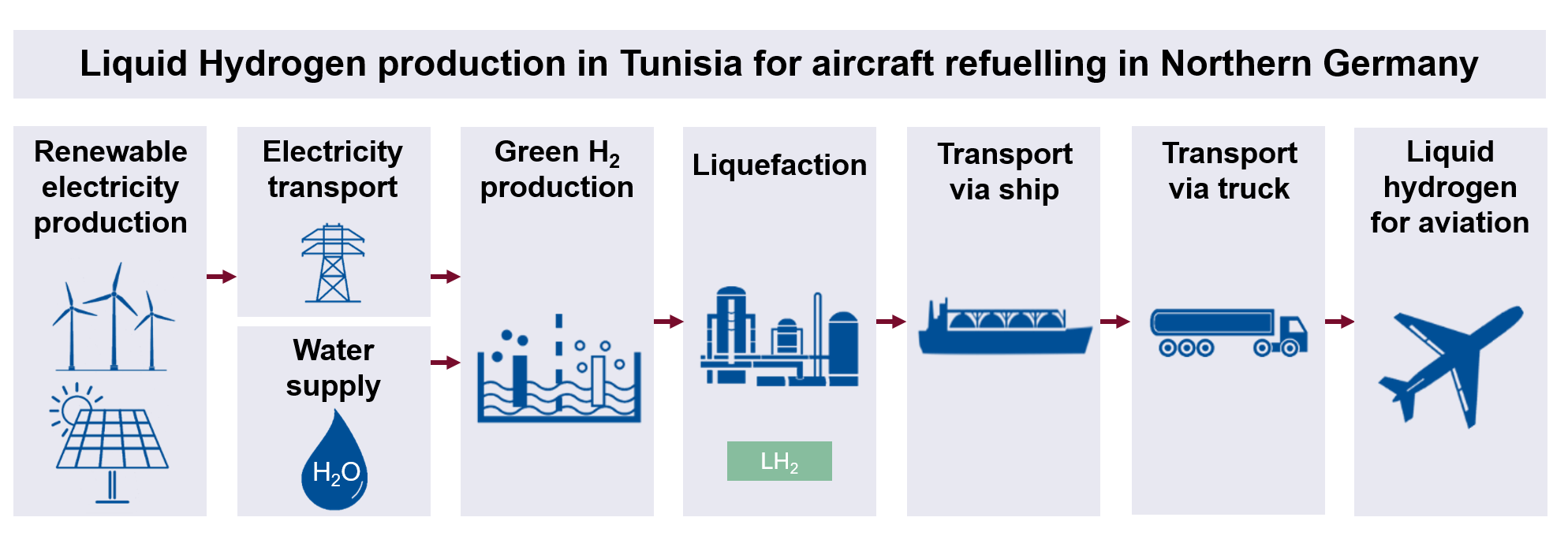

3. Example 2: Transport of liquid hydrogen via ship

Since the boil-off losses that occur during the storage of liquid hydrogen (as described in Chapter 3.2) increase with the duration of transport, liquid hydrogen-based supply chains are less suitable for very long transport distances. For the assumed supply of liquid hydrogen to an airport in Northern Germany, Tunisia is chosen as an export country becuase it is relatively close to Central Europe. Large-scale seasonal hydrogen storage is not used in this example for two reasons. Due to its geographical location, the seasonal fluctuations in the availability of renewable energies in Tunisia are significantly lower than in most parts of Europe. In addition, the boil-off losses already mentioned would be high if liquid hydrogen were to be stored for long periods of time.

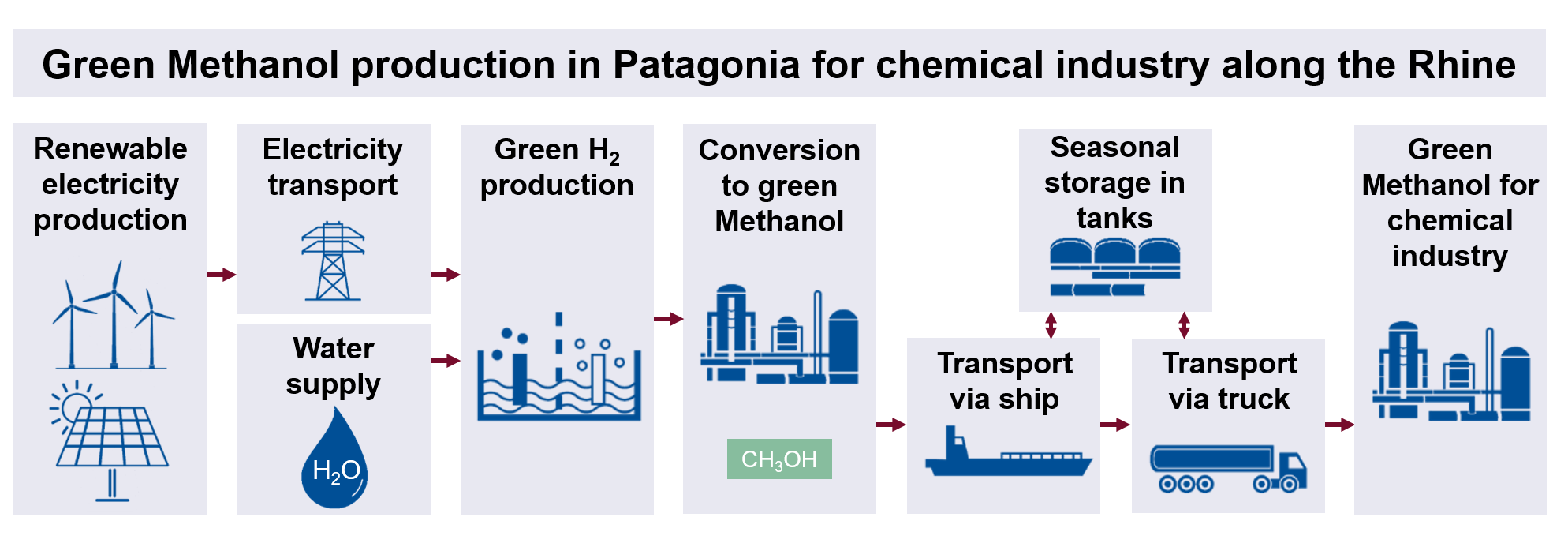

4. Example 3: Transport of green methanol

Due to its good transport properties, green methanol may also be imported from very distant regions in the future. Since methanol, unlike liquid hydrogen, can be transported by ship almost without losses, the transport costs barely contribute to the overall costs, irrespective of the distance to be covered. For the supply chain illustrated here, Patagonia was chosen as an exemplary export region, where green hydrogen and its derivatives can potentially be produced at low cost due to very favourable wind conditions.

In the schematic representation of the supply chain, the supply of carbon dioxide for methanol synthesis was neglected for reasons of clarity. However, the availability of green carbon dioxide may be an important criterion for the selection of sites for the production of green methanol in the future. It is conceivable, for example, that regions that have a large biomass potential - and thus at the same time a high availability of green carbon dioxide - have decisive location advantages with regard to the production of green methanol compared to regions without such a biomass potential.

5. Expert lecture

Hydrogen supply chains – Options and their assessment