Global Supply Chain and Logistics

| Website: | Hamburg Open Online University |

| Kurs: | MoGoLo - Mobility of Goods and Logistics Systems |

| Buch: | Global Supply Chain and Logistics |

| Gedruckt von: | Gast |

| Datum: | Dienstag, 3. März 2026, 06:19 |

Beschreibung

The topic “Global Supply Chain, Logistics and Sustainability” provides you with an overview of the topic cluster “Mobility of Goods and Logistics Systems” (MoGoLo) and its learning objectives. In all topics of this topic cluster we provide you with tools to understand and to design supply chains with as much sustainable standards in logistics as possible.

1. Introduction

This topic gives you a first insight into the topic of "Mobility of Goods and Logistics Systems" and its most important definitions. Besides that, you will get to know what you need to take into account while designing a supply chain. Because all kind of transport is having an environmental impact, we will show you, what measures can be taken to reduce this negative impact.

- to make the related functions and processes more efficient and more reliable, and

- also to reduce its impact on society or the environment

First, you will learn some basic definitions for understanding the topic cluster ”MoGoLo” better. Afterwards, the conceptual system model of transport and traffic will be introduced. As this system model is used to structure topics 3 – 7, it is presented in detail in topic 2. Based on this underlaying understanding you will learn how to design a supply chain and what needs to be taken into account while doing so. As all kind of transport is having an environmental impact, the last chapter of this topic will give you more information about the ecological dimension of goods movement and possible measures to reduce this impact.

A PC from around the world

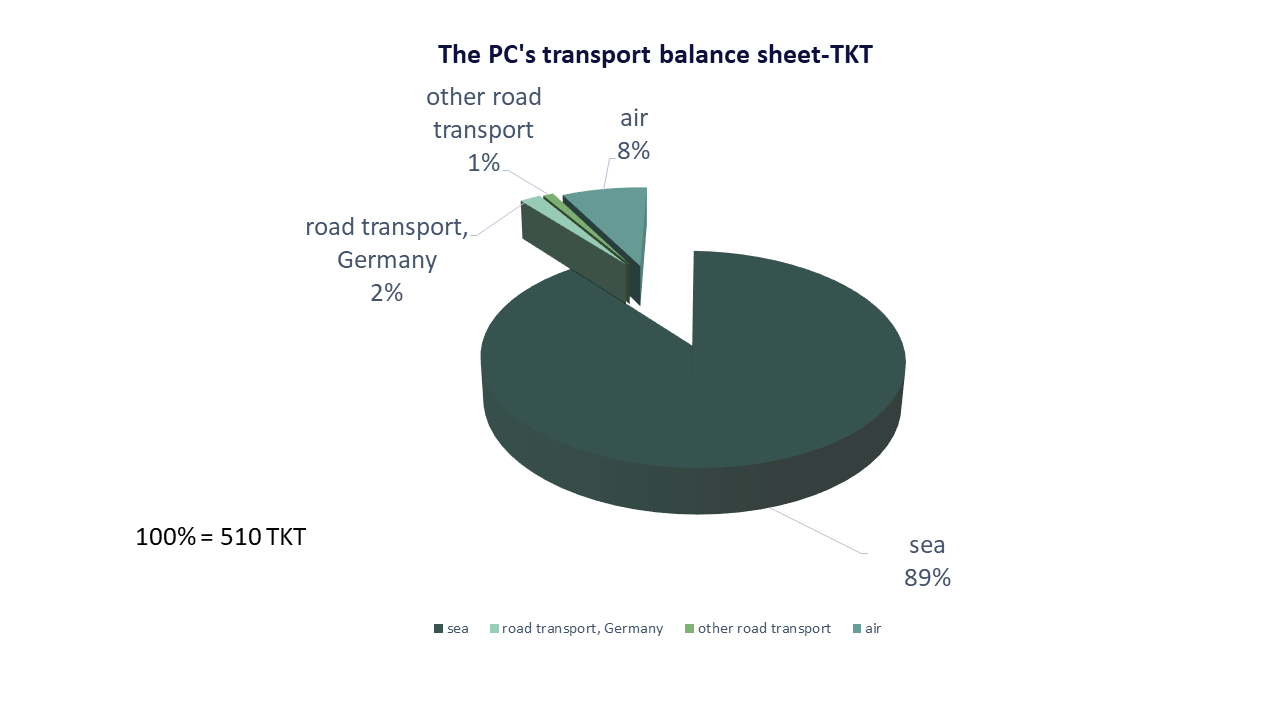

The PC‘s transport balance sheet – TKT

- The diagram "A PC's transport balance sheet" (TKT) shows the sum of tonne kilometres transported of all parts and components as well as of the finished computer. In total all transport processes of the PC and all its parts amount to 510 TKT.

- Nearly 90 percent of the total TKT is covered by container vessels due to long distance transports and heavy goods.

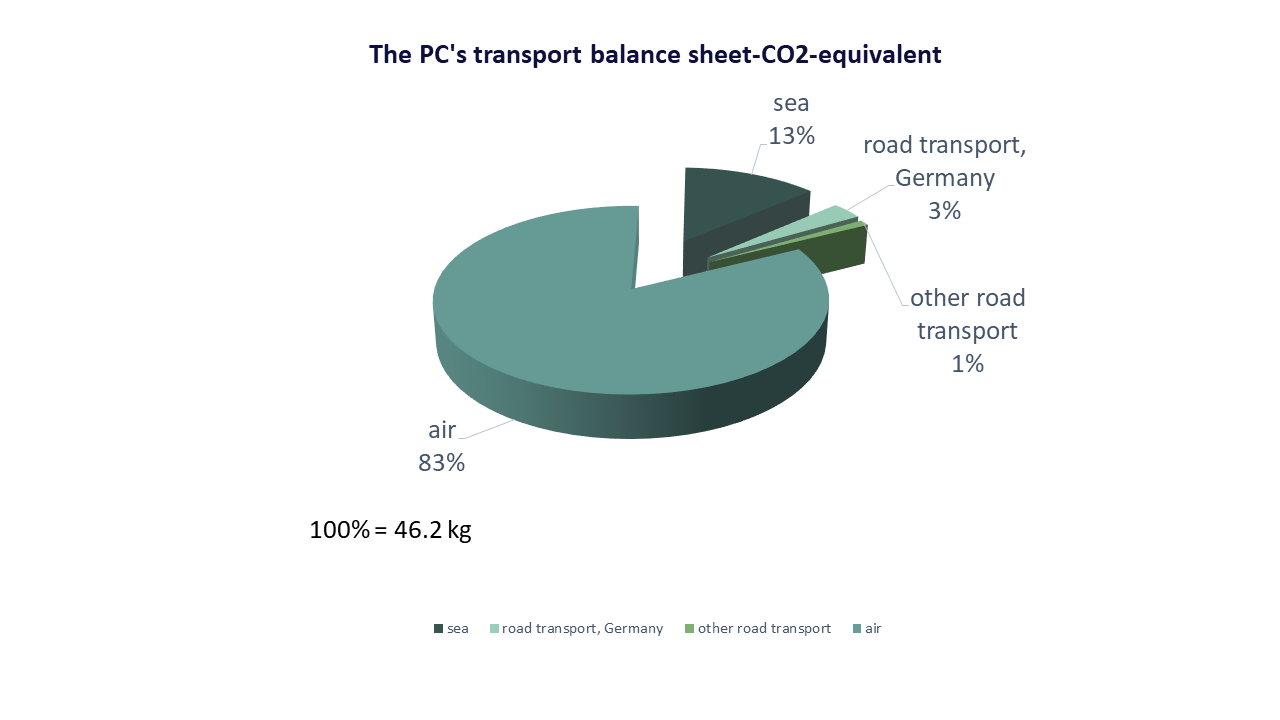

The PC's transport balance sheet - CO2-equivalent

- The transport of the PC is emitting CO2.

- In total the PC has a “climate relevant backpack” from 46.2 kg of CO2 emissions.

- The diagram "A PC's transport balance sheet - CO2" shows that most of the climate relevant impacts result from the transport with airplanes.

- Compared to the previous figure, it is clear that the decision for one mode of transport from an economic point of view is different from an ecological one.

Literature

- Kerkhoff, C. (2004): Standortverflechtungen und Verkehrsaufkommen bei Herstellung und Vertrieb eines Personalcomputers. Unpublished Thesis TU Dortmund University. Own translation

2. Basic definitions

To better understand the topics in MoGoLo, this page will provide you with some basic definitions for logistic relevant terms.

Transport chain

Logistics

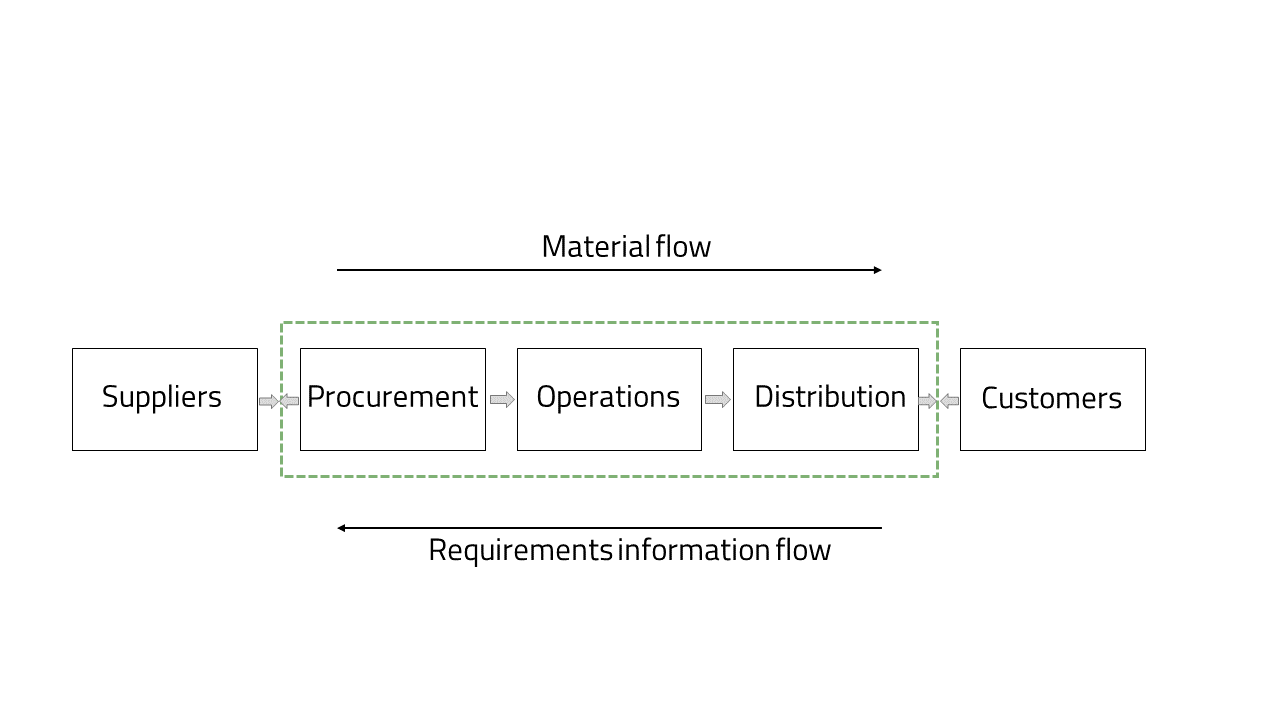

The figure "Logistics management process" shows the whole process including the different stages of the logistics management process (suppliers, procurement, operations, distribution, customers).

Third party logistics:

From company logistics to supply chain management

the efficient, effective forward and reverses flow and storage of goods, services and related information between the point of origin and the point of consumption in order to meet customers' requirements.

CSCMP’s boundaries and relationships of logistics management

Now you know the most important definitions for logistics.

- Christopher, M.(1998): Logistics and Supply Chain Management 2.Ed. p. 4, 13

- Coyle, J.J.; Bardi, E.J.; Langley, J.C. (2003): The management of Business Logistics: A Supply Chain Perspective. Canada.

- Thomsom South-Western CSCMP (Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals) (2021): CSCMP Supply Chain Management Definitions and Glossary. URL: https://cscmp.org/CSCMP/Academia/SCMDefinitionsandGlossaryofTerms/CSCMP/Educate/SCMDefinitionsandGlossaryofTerms.aspx?hkey=60879588-f65f-4ab5-8c4b-6878815ef921 (last access: 29.06.2021)

2.1. Quiz - Basic definitions

3. Conceptual system model of transport and traffic

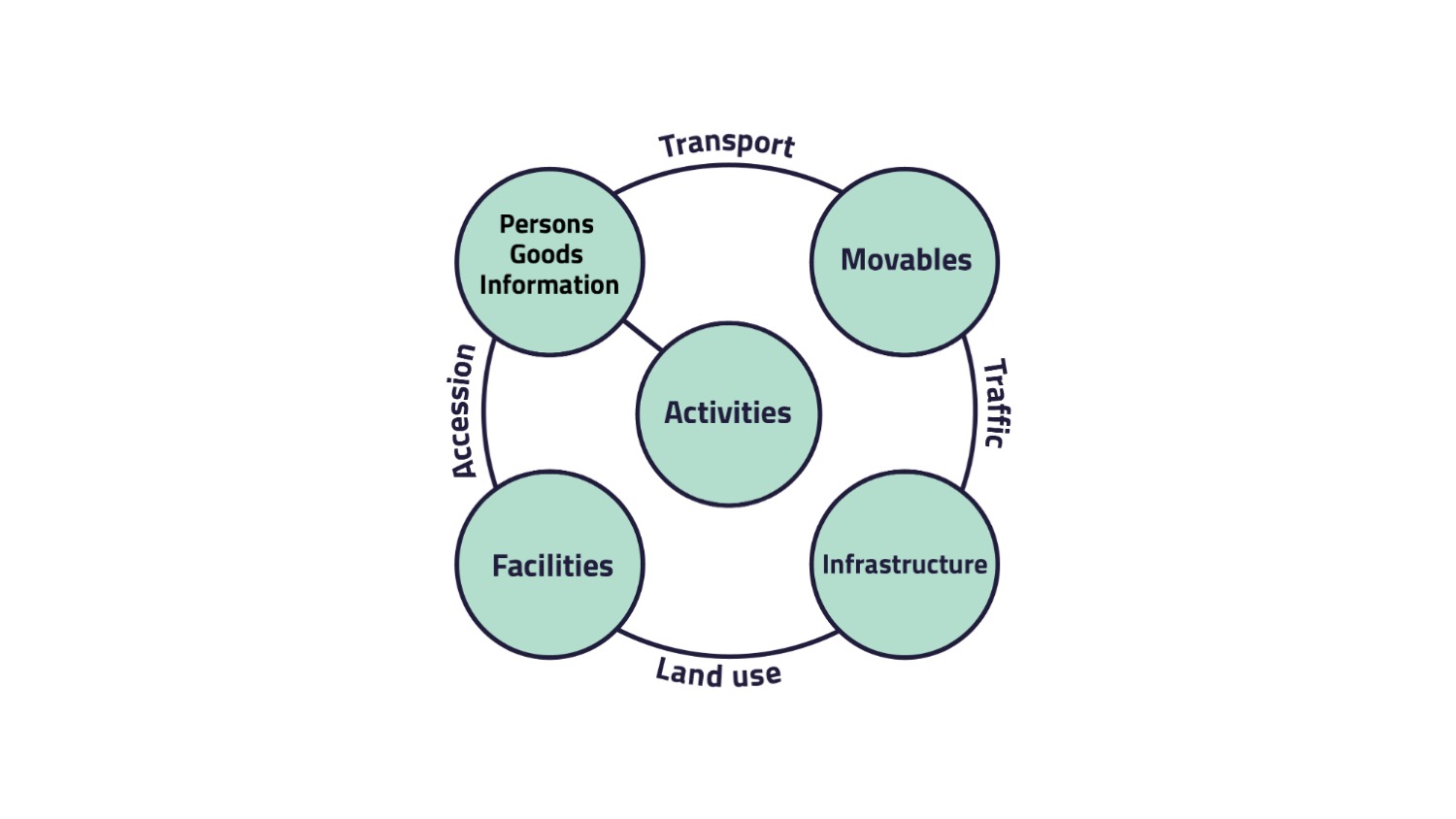

Now that you understood the definitions, this page introduces you to the conceptual system model of transport and traffic, which is shown in the figure "Conceptual system model" below.

Literature

- Flämig, H.; Sjöstedt, L.; Hertel, C. (2002): Multimodal Transport: An Integrated Element for Last-Mile-Solutions? Proceedings, part 1; International Congress on Freight Transport Automation and Multimodality: Organisational and Technological Innovations

- Sjöstedt, L. (1996): A Theoretical Framework – from an Applied Engineering Perspective. In: Eurocase - Mobility, Transport and Traffic: in the perspective of growth, competitiveness, employment. Paris, France.

4. Design of the supply chain

On this page, you will learn, how to design a supply chain and what different aspects need to be considered in this complex process.

- Typical vehicles for long distance transport are airplanes and seagoing vessels, for regional transport inland waterway vessels, trains and trucks.

- For the last mile delivery vans are common.

- The transshipment between the transport vessels takes place in logistic nodes, as ports, airports or other freight terminals.

How do logistics strategies influence the freight transport system?

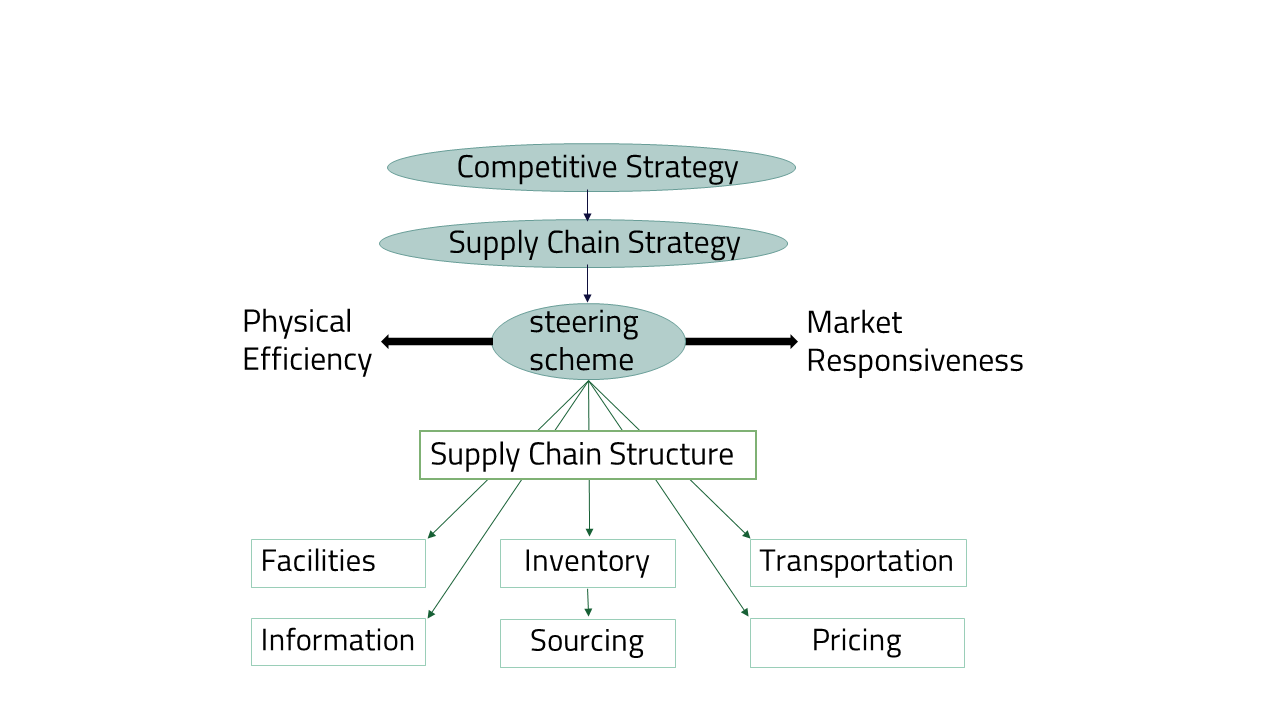

Supply chain strategies

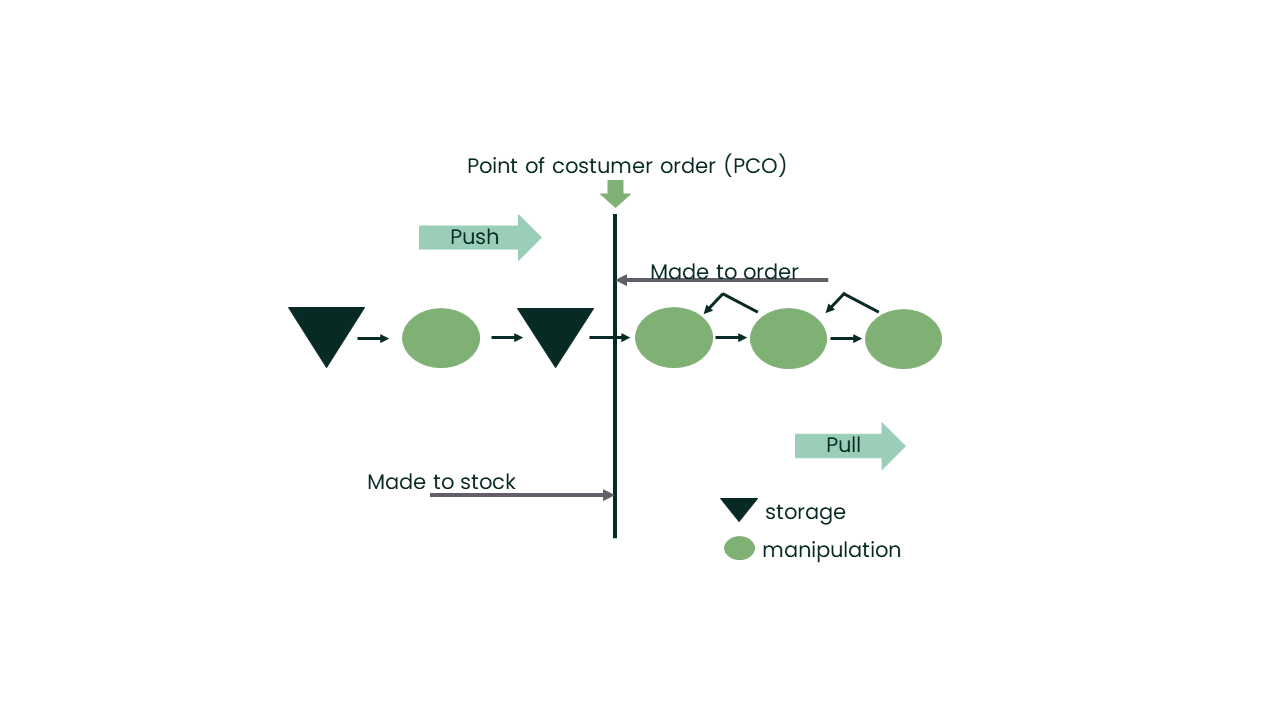

Steering schemes

- the reduction of stocks throughout the supply chain and thereby, the reduction of the so-called "Bullwhip-Effect" (physical efficiency)

- avoiding out-of-stock-situations and associated opportunity costs (market responsiveness).

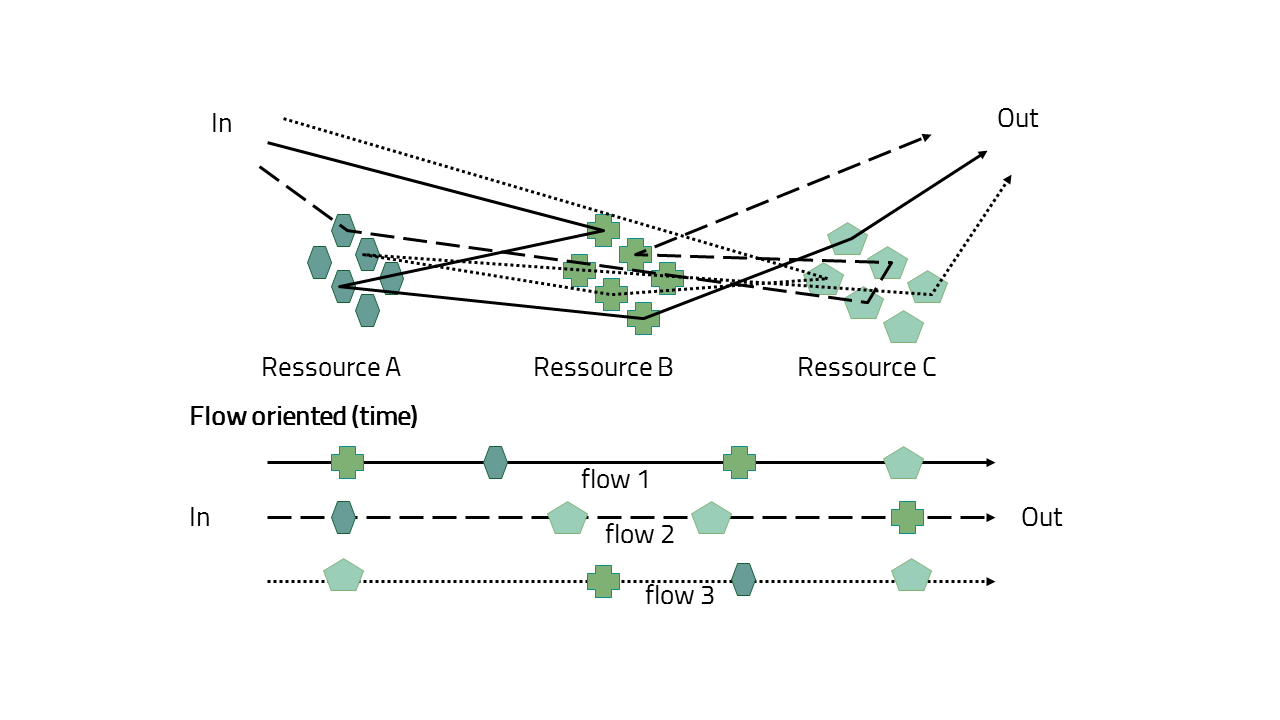

- the temporal adjustment of the value adding processes (time based) via flow-oriented or resource-based (functional) approaches;

- the nature of the order, further distinguished by push and pull steering modes.

- the magnitude of freight flows,

- its temporary urgency and

- patterns of spatial distribution of those activities required to cope with the demand.

Resource or flow oriented

- In the flow-oriented approach, steering is organized via the time that is required for certain tasks to be done. The central steering parameter is the lead time which has to be kept at a minimum.

- In the resource-oriented approach, steering is organized via the available capacities of resources and the time that is required for getting certain tasks done; these capacities can comprise e.g., machinery or staff capacity.

- In logistic transport systems, this approach is of importance for large logistics nodes, such as harbours, freight transport centers, goods distribution centers with major warehouses and consolidation outlets. They tend to be crucial for the functionality of these nodes. However, some specialized interfaces may only be suitable for meeting very specific demands.

- A standardized production system, which is found in the case of hubs of courier, express and postal (CEP) service providers, is adjusted to a consistent use of capacity with standardized shipment (dimensions, weight) and covers only forwarding (no storage or commissioning) and the function of consolidating transport.

Push- or pull-oriented

At this point, the final product is individualized and in most cases its destination is known.

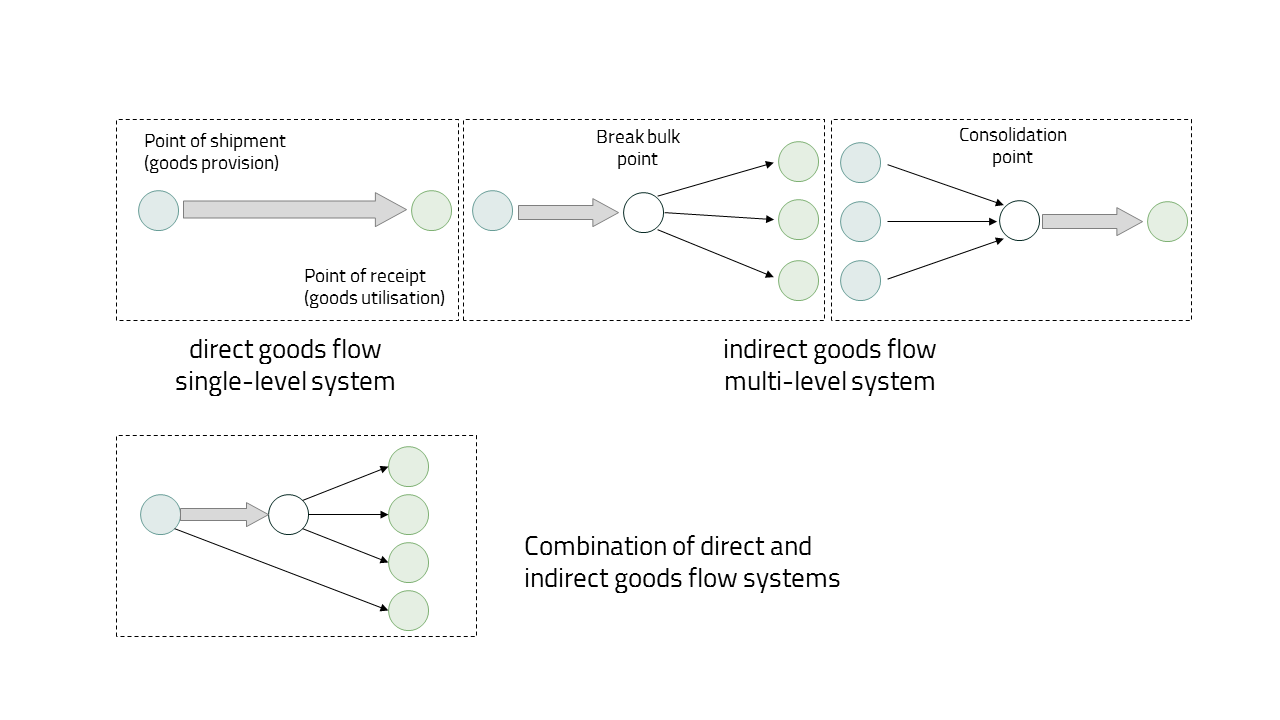

Supply chain structure

In indirect flow systems the goods flow is interrupted by various trade levels, changing loading units or transport mediums in order to bundle shipments (consolidation) and thereby, increasing the efficiency of the system. Thus vehicles can be used to their full capacity. Additionally, more efficient means of transportation can be used. Concerning transport management, transport is either realized through direct transport or through grid patterns or so-called "Hub-and-Spoke" (HuB)-Systems. In grid patterns, handling points are exclusively connected by direct transport. In the case of general cargo, cooperation’s are often organized this way.

- Bowersox, D.J.; Closs D. J.; Cooper M. B.; Bowerbox, J. C. (2007): Supply Chain Logistics Management. 2nd Edition. McGraw-Hill/Irwin, NY.

- Chopra, S.; Meindl, P. (2016): Supply chain management (3. ed., Pearson internat. ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Hopp, J. W.; Spearman, M. L. (2001): Factory Physics: Foundations of Manufacturing Management. 2nd Edition. McGraw-Hill/Irwin, NY

- Löwa, S.; Flämig, H. (2011): Integration of Logistics Strategies in Urban Transport Models In: Conference Proceedings of 4th METRANS „National Urban Freight Conference“, Long Beach, CA (USA)

- Pfohl, H.-C.(2004): Logistiksysteme - Betriebswirtschaftliche Grundlagen, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, Springer-Verlag, 7. Auflage.

- Sharman, G. (1984): The rediscovery of logistics. Harvard Business Review 62(5)

4.1. Quiz - Impact of the supply chain

In order to examine, if you understood everything, you can test yourself by answering the following question:

5. Literature

Bowersox, D.J.; Closs D. J.; Cooper M. B.; Bowerbox, J. C. (2007): Supply Chain Logistics Management. 2nd Edition. McGraw-Hill/Irwin, NY.

Chopra, S.; Meindl, P. (2016): Supply chain management (3. ed., Pearson internat. ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Christopher, M. (1998): Logistics and Supply Chain Management. 2.Ed.

Coyle, J.J.; Bardi, E.J.; Langley, J.C. (2003): The management of Business Logistics: A Supply Chain Perspective. Canada. Thomsom South-Western.

CSCMP (Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals) (2021): CSCMP Supply Chain Management Definitions and Glossary. URL: https://cscmp.org/CSCMP/Academia/SCM_Definitions_and_Glossary_of_Terms/CSCMP/Educate/SCM_Definitions_and_Glossary_of_Terms.aspx?hkey=60879588-f65f-4ab5-8c4b-6878815ef921 (last access: 29.06.2021).

Flämig, H. (2015): Logistik und Nachhaltigkeit.

In: Heidbrink, Ludger; Meyer, Nora; Reidel, Johannes; Schmidt, Imke

(Hrsg.): Corporate Social Responsibility in der Logistikbranche-

Anforderungen an eine nachhaltige Unternehmensführung. Berlin: E.

Schmidt, 2015. S. 25-44.

Hopp, J. W.; Spearman, M. L. (2001): Factory Physics: Foundations of Manufacturing Management. 2nd Edition. McGraw-Hill/Irwin, NY.

Kerkhoff, C. (2004): Standortverflechtungen und Verkehrsaufkommen bei Herstellung und Vertrieb eines Personalcomputers. Unpublished Thesis TU Dortmund University (Own translation).

Kolding, Eivind (2008): An Ocean Carrier’s View of Current Trends. 25th German Logistics Congress 2008. Berlin, 24.10.2008.

Löwa, S.; Flämig, H. (2011): Integration of Logistics Strategies in Urban Transport Models. In: Conference Proceedings of 4th METRANS „National Urban Freight Conference“, Long Beach, CA (USA).

Pfohl, H.-C.(2004 ): Logistiksysteme - Betriebswirtschaftliche Grundlagen. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York. Springer-Verlag, 7. Auflage.

Sharman, G. (1984): The rediscovery of logistics. Harvard Business Review 62(5), 71–80.

Sjöstedt, L. (1996): A

Theoretical Framework – from an Applied Engineering Perspective. In:

Eurocase - Mobility, Transport and Traffic: in the perspective of

growth, competitiveness, employment. Paris, France.